EDITOR’S NOTE: Everyone has a story — some more well-known than others. Across Western North Carolina, so much history is buried below the surface. Six feet under. With this series, we introduce you to some of the people who have left marks big and small on this special place we call home.

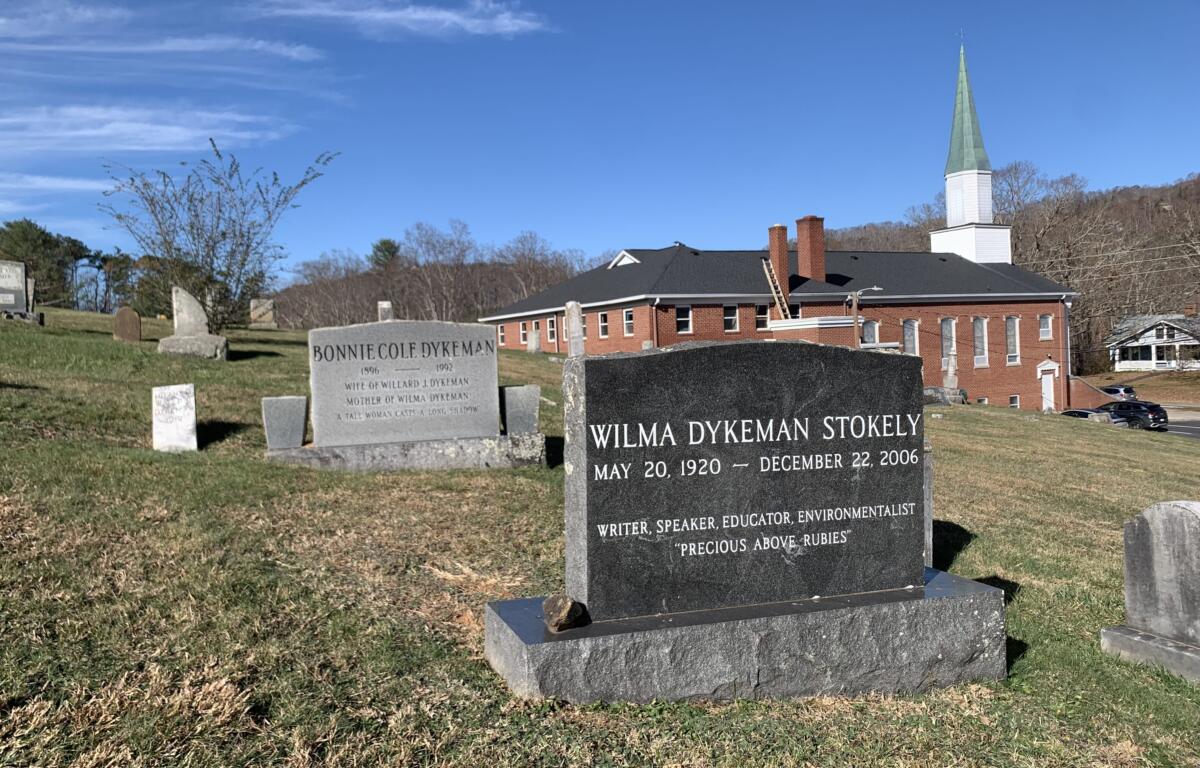

Wilma Dykeman Stokely (1920-2006), acclaimed author of 18 books, advocate and public speaker, who wrote “The French Broad,” is buried in the Beaverdam Baptist Church Cemetery in Asheville.

—–

The woman credited for saving the French Broad River from pollution and the founding of the River Arts District is buried in Asheville. Do you know her name?

Wilma Dykeman was born on May 20, 1920, a few miles north of Asheville in the Beaverdam Creek area. Her father, Willard Jerome Dykeman, was a retired dairy farmer from New York. Her stay-at-home mother, Bonnie Cole, was from a family that had been natives of N.C. since the eighteenth century.

An only child, Wilma was well educated, attending Grace Elementary and Grace High School, both in the village of the same name. Up Merrimon Avenue, Grace was around three miles north of downtown Asheville today.

Legend suggests Dykeman met another famous writer from Asheville, Thomas Wolfe, as a child. Wolfe was a known inspiration for her throughout her life.

Wilma’s imagination, as the story goes, began creating new worlds to write about from the time she was in elementary school. The sharp schoolgirl dabbled in script writing and poetry in her grade school years.

Dykeman attended Biltmore Junior College, which later became UNC Asheville. After two years there, she moved to Northwestern University in Illinois. to complete a bachelor’s degree in speech. Her acting professor lined up a teaching position for Dykeman in broadcasting at a new school in Manhattan.

But Dykeman got hitched.

While at Northwestern, she met James R. Stokely Jr., a fellow writer and poet from Newport, Tennessee. Stokely was an heir to a successful canning operation. When the couple graduated together in 1940, they got married in the front yard of Dykeman’s family home.

The Stokelys never left their mountainous hometowns, splitting their time between Asheville and Newport, where they raised their two sons. Dykeman would later collaborate on books with her boys.

After Stokely was unceremoniously forced out of the family business in a messy buyout, James and Wilma became apple farmers to supplement their income. Their articles and books paid well but were released irregularly. They owned orchards on both sides of the border, driving back and forth between their two homes often.

Between raising two sons and looking after the orchards, Dykeman found time to write, starting off with radio scripts. She would go on to write articles regularly for regional and national newspapers.

Her primary moneymaker was writing short stories for some of the largest magazines of the day including the New York Times Magazine and Reader’s Digest. “The Simple Life” was Dykeman’s longest running project, a column in the Knoxville News Sentinel running from 1962 to 2000.

In 1955, Dykeman released her first book “The French Broad.” It would become her most famous work.

“The French Broad” was part of the extensive catalog of the “Rivers of America” books, with hers being number 49 in the series. “Rivers of America” chonicled the history of the people who surrounded a specific river in the United States. In total, over 60 volumes were published between 1937 and 1974.

Seen as a cash cow for the New York publisher, Rhinehart & Co., “Rivers of America” was a sanitary and uncontroversial series. Rhinehart & Co. made a mistake by hiring Dykeman who had no intention of being sterile. She outright refused to have her text published without the inclusion of a controversial final chapter.

The chapter was titled “Who killed the French Broad?”

In it, Dykeman railed against the pollution in her beloved river, noting how it would only continue to worsen the lives and well-being of tourists and locals alike. She believed the river had been polluted by man’s selfishness and greed.

Rhinehart & Co. caved to Dykeman’s demands and printed the book unedited.

Canton’s Champion Paper factory had long been associated with the river’s pollution, which Wilma recognized and resented them for, but she knew there was a deeper issue at hand.

“There is only one respectable course for a free citizen and that is to shoulder his share of the responsibility for the ‘killing,’ for the pollution,” she wrote in the famous chapter. “Because, just as the river belongs to no one, it belongs to everyone and everyone is held accountable for its health and condition.”

Dykeman’s argument against polluting the river was probably better received than most environmentalist literature at the time because she did not stop at explaining the environmental damage, but also the economic. The health of the river, she explained, affected the pocketbooks of Asheville’s citizens and companies.

For many writers who have analyzed “The French Broad,” a direct comparison has been drawn to Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” which released seven years later. Dykeman and Carson shared an acute concern for the environment, and both have been cited for inspiring the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Her contribution to the “Rivers of America” series can be thought of as the combination of her many interests. Its topics include the history of the region mixed with folklore, sociology of the people she grew up with and heard tales from and the natural environment that bred the culture she loved.

Dykeman won the first annual Thomas Wolfe Memorial Literary Award for writing “The French Broad,” an award still given out yearly by the Western North Carolina Historical Association. Perhaps coincidence, perhaps not, Thomas Wolfe is featured prominently in Dykeman’s seminal work.

Due to her arousing public sentiment to clean the French Broad, the Asheville City Council voted in 2021 to name a park in the River Arts District the Wilma Dykeman Greenway. It stretches for 17 miles down the banks of the Swannanoa and the French Broad. Hurricane Helene significantly damaged the greenway in Sept. 2024.

After the success of “The French Broad,” Dykeman wrote another 17 books, both novels and nonfiction. She wrote mostly about her experience in Appalachia.

Apart from “The French Broad,” Dykeman is remembered for books like “The Far Family,” “Return the Innocent Earth” and “Neither Black nor White,” the latter a text on race relations co-authored with her husband. “Neither Black nor White” won the Sydney Hillman book of the year award for exploring sentiments in the aftermath of the Brown vs. Board of Education decision by the United States Supreme Court.

She wholeheartedly believed literature was the pathway to the respect of human dignity and change. “What has usually stirred societies, historically, to action?” Dykeman once wrote. “We had any number of reports about slavery, but it was Uncle Tom’s Cabin that lit the fuse.” The book she references is largely credited as arousing abolitionist sentiments in the North, leading indirectly to the Emancipation Proclamation. She hoped her own books might do the same for environmentalism and race relations.

Of the 18 books she wrote, Dykeman’s personal favorite was “Return the Innocent Earth,” was a thinly veiled rant about the injustice in her husband’s family business as it ceased to be a family business, railing against the genetically modified organisms the corporation was using.

The Stokely Canning Co., later Stokely-Van Camp, was a large food processing company, with around 70 facilities by the 1960s. The company canned the still popular Van Camp Pork and Beans, packed tomatoes and bottled Gatorade. By the 1990s, the food powerhouse once owned by Quaker Oats was split in two. Stokely was acquired by Red Gold and ConAgra bought Van Camp. Each still holds those brands today.

James Stokely, Jr. died of a heart attack in 1977, nearly 30 years before his wife.

Following her husband’s death, Dykeman remained busy, serving as an adjunct professor at Berea College and the University of Tennessee for several decades. At UT, she taught a popular course on Appalachian Literature in the Spring term.

Lecturing for Dykeman was not confined to the classroom. As a public speaker, Dykeman delivered around 75 speeches each year on subjects like conservation, history, race, women’s rights and her greatest passion, literature.

“The First Lady of Appalachia Literature,” as she had come to be called, celebrated the nation’s birthday by writing “Tennessee: A Bicentennial History,” an encyclopedia of the growth and development of her second home state.

In 1981, Dykeman was named the Honorary Tennessee State Historian by the state legislature, retaining the title until her death.

Supposedly, when the Houston Oilers moved to Nashville, Dykeman was chosen to sit on the naming commission. According to UNC Asheville’s Wilma Dykeman Writer-in-Residence Program, it was Dykeman that coined the name “Tennessee Titans” in honor of Music City’s other nickname, “The Athens of the South.”

Throughout her long life, long enough to watch cattle drives through Pack Square en route to southern markets and the rise of the internet, Dykeman was endowed with many awards.

In 1985, Dykeman was bestowed with the Guggenheim Fellowship, a grant given to authors with a high degree of literary achievement. She is one of 175 to receive the honor since its inception in 1925.

Thirty years after the publication of “The French Broad,” Dykeman became a recipient of the North Carolina Award for Literature.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, Dykeman began experiencing resistance from her memory, using a diary to help her remember. By 2003, her condition had deteriorated enough that she was moved to an assisted living facility in Asheville.

Wilma Dykeman Stokely died of complications from a hip surgery on Dec. 22, 2006, at age 86 in Asheville. She is buried in the graveyard of what was Beaverdam Baptist Church, about two miles north of the Omni Grove Park Inn. Today, the congregation who meets there is called REVOL Church.

189 Lynn Cove Road is where the Stokely’s once resided. Today, it houses UNC Asheville students as part of the Writers-in-Residence Program.

“The Writer-in-Residence Program’s mission is to increase awareness of the core values and body of work of Wilma Dykeman and to contribute to local, regional, and national conversations with original works of fiction, non-fiction, and other media which center around the causes Wilma spent her life supporting,” according to the program’s website.

UNC Asheville’s Writer-in-Residence Program offers housing for two months and a $4000 stipend to recipients chosen based on their desire to write. While they welcome writers from all genres to apply, the residency is intended for authors focusing on “social, racial, gender, and/or environmental issues.”

Writer-in-Residence is one of several projects funded by the Wilma Dykeman Legacy foundation. Wilma’s son, Jim Stokely, heads the organization.

The foundation’s website explains its mission in this way. “The Wilma Dykeman Legacy is a non-profit organization that develops and sponsors diverse and inclusive talks, workshops, events, books, and other programs, products and services to sustain the core values for which Wilma Dykeman stood: environmental integrity, social justice, and the power of the written and spoken word.”