EDITOR’S NOTE: Strangeville explores the curious and unexplained stories that have long defined Asheville and Western North Carolina. The region is full of unanswered questions, from old folklore and local legends to eerie encounters, unsolved moments in history, and the true-crime mysteries that still leave people wondering. Each week, we look back with an open mind and a sense of curiosity, trying to understand why some stories take hold and why some can never be explained.

Asheville holds the distinct honor of being one of the few cities presidential candidates consistently visit during their campaigns. That tradition began almost 130 years ago.

Joining the list of cities who have seen a presidential candidate in person in 1896, the people of Asheville welcomed the arrival of Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan. Two decades later, the three-time presidential nominee bought land from one of the city’s most powerful families and built a home that remains standing today.

Early Life

According to the United States Office of the Historian, William Jennings Bryan “was born in Salem, Illinois on March 19, 1860. He graduated from Illinois College in 1881, and from the Union College of Law in 1883. He was admitted to the Illinois State Bar in 1883 and practiced law in Jacksonville, Illinois prior to moving to Lincoln, Nebraska in 1887.”

Before the move to the Midwest, Bryan married Mary Elizabeth Baird in 1884. The couple would go on to have three children.

Political Career

A tireless advocate of populist ideals, Bryan accrued the moniker “the Great Commoner” for his championing of policies aimed at serving the farmer and working man. “He was influential in the eventual adoption of such reforms as popular election of senators, income tax, creation of the Department of Labor, Prohibition, and women’s suffrage,” according to Britannica.

In 1890, Bryan was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives serving the constituents of Lincoln, Nebraska. He served two terms before leaving his post to mount an unsuccessful run for a Nebraska senator seat.

In 1896, Bryan secured the Democratic nomination for president at age 36 after giving a legendary speech titled “Cross of Gold.” He lost the general election to Republican candidate William McKinley.

During his failed campaign, Bryan stopped in several cities in Western North Carolina, including one which would adore him for the rest of his life.

“Bryan Day – the greatest event, politically at least, in the history of Asheville and Western North Carolina,” opened the cover story on the Asheville Daily Citizen on Sept. 16, 1896. That day marked the first time a presidential candidate had visited Asheville. “The Earth almost shook with the cheers for Bryan,” the reporter wrote. Bryan’s campaign rally in Asheville spawned a tradition which carries on to today of candidates campaigning here.

Bryan achieved the rank of colonel during the Spanish-American War in 1898. The former and future Democratic presidential candidate served in the 3rd Nebraska Infantry Regiment. The conflict incited pacifist sentiments within Bryan which he would harbor for the rest of his life.

Bryan’s political ambitions did not abate after his 1896 presidential loss, going on to run for the presidency two more times on the Democratic ticket in 1900 and 1908. In 1912, Bryan’s advocacy for Woodrow Wilson secured him the nomination.

During Wilson’s presidency, Bryan was appointed as the forty-first Secretary of State. As an avowed pacifist during the outbreak of the Great War, Bryan was unfit for the role president gave him. The three-time presidential candidate stepped down after the sinking of the Lusitania.

Bryan and Asheville

A frequent vacationer in the area, Bryan was no stranger to the Blue Ridge Mountains.

At the opening ceremony of the Grove Park Inn on Jul. 1, 1913, Bryan was both the guest of honor and principal speaker. Friendly with the Grove family, Bryan began to acquire land near their hotel, some of which he purchased from the family directly.

In Sep. 1917, construction began on Bryan’s Asheville residence, which had been designed in the Colonial Revival style by Biltmore architects Smith and Carrier.

The application filing for Bryan’s house to enter the National Historic Register, states, “One can imagine Bryan, the Great Commoner, directing English-born, Beaux-Arts-influenced R. S. Smith, who usually designed in an old English vocabulary, to give him a solidly traditional, solidly American home for his retirement years.”

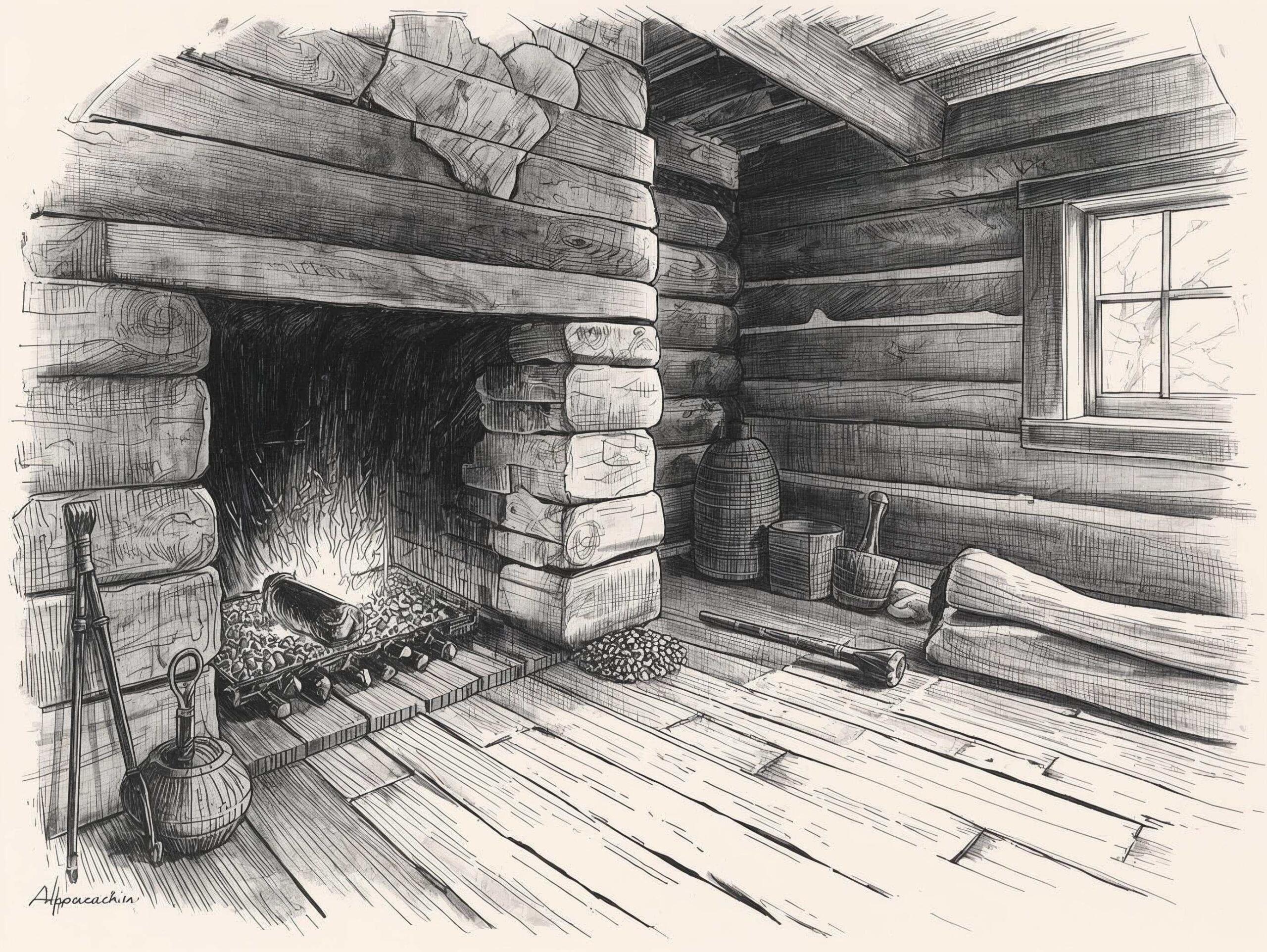

Situated at the southern end of the Grove Park Inn’s golf course, the white two-story house includes four bedrooms, three bathrooms, two half bathrooms, five fireplaces “heart pine flooring, boxed redwood beams, open kitchen, formal dining, libraries… workshop, gazebo [and] gardens on double lot,” according to GreyBeard Reality, who recently sold the 3,412 square foot dwelling, with the asking price set at $869,000.

While his residence in Asheville was short, Bryan saw the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment while in his mountain home. The constitutional amendment barred the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors,” a measure which he had fought for decades to pass.

Bryan did not use the house for long, selling it in 1920. Apparently, the Asheville weather did not agree with his wife’s health.

Since 1987, the house has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. At least two other homes of the statesman have been preserved, those being in Salem, Illinois and Lincoln, Nebraska.

While a private residence, the Bryan house is still publicly accessible on sidewalks for viewing of the exterior at 107 Evelyn Place.

The Final Crusade at the Scopes Trial

After being introduced onto the floor of the Tennessee House of Representatives by John W. Butler, the so-called “Butler Act,” according to History.com, “was passed six days later almost unanimously with no amendments.”

The Butler Act outlawed the teaching of the theory of evolution in public schools statewide. Thinking the new law was unconstitutional, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) vowed to fight any case that involved it.

John Scopes was a high school math and physics teacher in Dayton, Tennessee. Even though he was not a biology teacher, the ACLU convinced Scopes he had taught his pupils enough about the theory of evolution to violate the law.

Bryan was well-known by this point for his anti-evolution stance. He was the natural choice for the case. Clarence Darrow, on the other hand, was the second pick. Initially, the ACLU had offered the defense attorney position to science fiction author H.G. Wells, but he declined. Darrow was a well-known lawyer and leading member of the ACLU from Chicago. He had sparred on matters of faith with Bryan publicly before.

The Scopes Trial, as it is most often called, has also been referred to as the “Monkey Trial” due to both the shenanigans occurring inside the courtroom and the literal circus monkey outside it. A carnival atmosphere ensued with concessions and merchandise retailers popping up in the small Tennessee town selling food and souvenirs for the once in a lifetime event.

John T. Raulston, the presiding judge, was helpless to stop the media frenzy. Stenographers broadcasted the words of Bryan and Darrow nationwide, sensationalizing what should have been a menial dispute with a banal outcome. Bryan and Darrow did everything they could to ham up the debate, each arriving in Dayton to defend their respective worldviews to the newspapers covering the court proceedings.

After several days of arguments, the trial concluded in perhaps the strangest way possible. Darrow called Bryan to the stand as an expert witness to testify on the validity of the Bible.

On Jul. 21, 1925, closing arguments were heard. In only nine minutes of deliberation, the jurors found Scopes guilty, fining him $100, almost $2000 in today’s money. Scopes would never pay.

The United States Supreme Court picked up the case later that year. They ordered the fine be revoked due to being excessive yet upheld the Butler Act as constitutional.

The Butler Act was eventually repealed by the Tennessee State Legislature in 1967.

Despite winning in the legal system, Bryan and his followers would be categorized by some media as backward, Bible-thumping fundamentalists. A play and later a film called “Inherit the Wind” depicts the Scopes Trial with Bryan appearing as a befuddled old man stumbling through sentences and making a fool of himself. Scopes is shown to be innocent and pure, and Darrow is a proud, yet heroic figure.

Death of the Great Commoner

The trial concluded. Bryan was tired. The media buzz and hot summer weather took a toll on his aging body.

Only five days after the verdict, the three-time presidential nominee had a stroke and died in his sleep on Jul. 26, 1925.

“W.J. Bryan Found Dead in Bed,” read the headline of the Asheville Citizen on Jul. 27, 1925, a shock and horror for all who picked up the paper that day. “William Jennings Bryan, probably the world’s greatest citizen, was found dead in his bed, Dayton, Tenn., yesterday afternoon,” the front-page laments. “Mr. Bryan once resided in this city where he is greatly admired by a host of thousands of friends.”

For the two days following Bryan’s death, most of the front page of Asheville’s newspapers were covered in outpourings of praise for and grief at the nation’s loss. Asheville’s city fire bell tolled 65 times to mourn the death of the 65-year-old.

Former Secretary of State Col. William Jennings Bryan was taken in a funerary train car from Dayton to the nation’s capital to be buried in Arlington National Cemetary on Aug. 1, 1925. His wife was laid beside him in 1930.