EDITOR’S NOTE: Western North Carolina is weird – and it always has been. From Cherokee myths to Bigfoot and alien encounters, the Blue Ridge Mountains host the quirky and bizarre from past and present. We would not have it any other way, and neither would you. Join us in unfolding the histories and unraveling the mysteries of this strange land we call home.

___

Cherokee folklore is written in stone in a very tangible way in Cullowhee, just outside the campus of Western Carolina University (WCU).

Nestled amidst the Balsam Mountains in Jackson County, the Judaculla Rock evades archeological understanding to this day. As erosion rapidly deteriorates the petroglyph decorated soapstone boulder, researchers are running out of time to study what is supposedly the largest collection of petroglyphs east of the Mississippi.

The myth of Judaculla

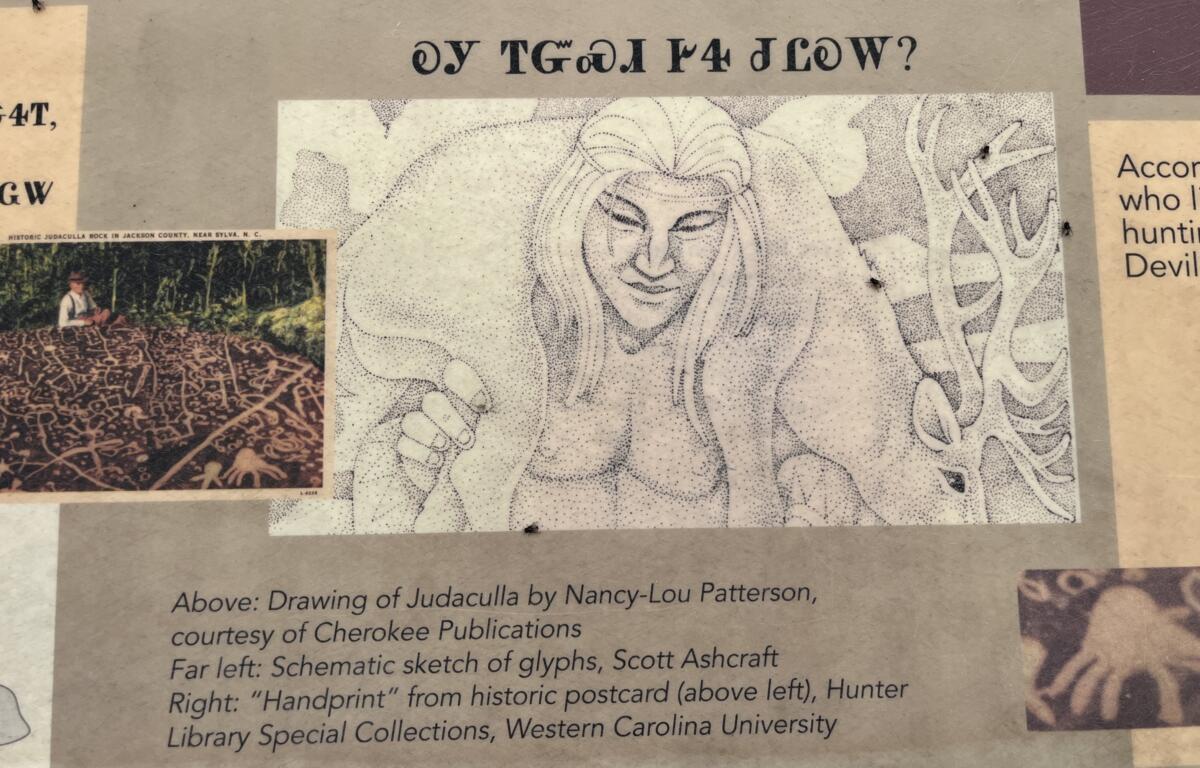

Most of what is known about the legend of the giant named Judaculla originates from ethnologist James Mooney’s “Myths of the Cherokee,” published in 1902. Despite being more than 100 years old, Mooney’s work is still considered contemporary because there are no more recent sources of a similar degree of scholarship. Most author since draw directly from his work, including the interpretive plaques surrounding the Judaculla Rock.

Judaculla is an anglicized corruption of the Cherokee “Tsul-ka-lu.” Mooney explains on page 477, “The name signifies literally ‘he has them slanting,’ being understood to refer to his eyes.” He continued, “In the plural form it is also the name of a traditional race of giants in the far west.”

Judaculla was said to be seven feet tall, hairy and so ugly that villagers could not bear to glance at his figure. In one story, Judaculla masks his deformities by turning himself invisible. He had seven digits on each extremity and was very strong. With great force, he once jumped eight miles, landing with his hand on the Judaculla Rock, leaving a handprint behind. As Mooney writes on page 407, “the Judaculla rock, a large soapstone slab covered with rude carvings, which, according to the same tradition, are scratches made by the giant in jumping from his farm on the mountain to the creek below.”

Judaculla was lonely, Mooney explains, resolving to find a wife in the nearby Cherokee village of Kanuga. From pages 337-341, he explains Judaculla found an eligible young lady, but her mother would only let her marry a hunter. From then on, every night that Judaculla visited, he would bring more meat than the mother and daughter needed.

One day, the mother asked to meet Judaculla, for to that point he had refrained from appearing during waking hours. Mooney writes, “and there she saw a great giant, with long slanting eyes, lying doubled up on the floor, with his head against the rafters in the left-hand corner at the hack, and his toes scraping the roof in the right-hand corner by the door.” Petrified by the beast before her, the mother ran away in fear. This enraged Judaculla, packing up his wife and their child. Fleeing to one of the Balsam Mountains, they joined an underground village with other Cherokee. From then on, Judaculla only appeared when a hunting party crossed the line on the Judaculla Rock. The Tanasee Bald was his hunting ground and his alone. Trespassing would be adjudicated at Devil’s Courthouse, named after the giant. According to Mooney on page 479, “a tradition among the pioneers that it was regarded by the Indians as the special abode of the Indian Satan!” Mooney personally maintained that Judaculla was a caring, yet insecure creature due to his appearance.

The Judaculla Rock

There are roughly seven geological features near Cullowhee that bear the giant’s name in some form or another. Names are as obvious as Judaculla Mountain and the Judaculla Old Field. Others, like Cullowhee itself, are derived from the giant’s name. This is more apparent when the two words are phoneticized: Cull-a-whee and Ju-da-cull-a. Both include “cull-a.”

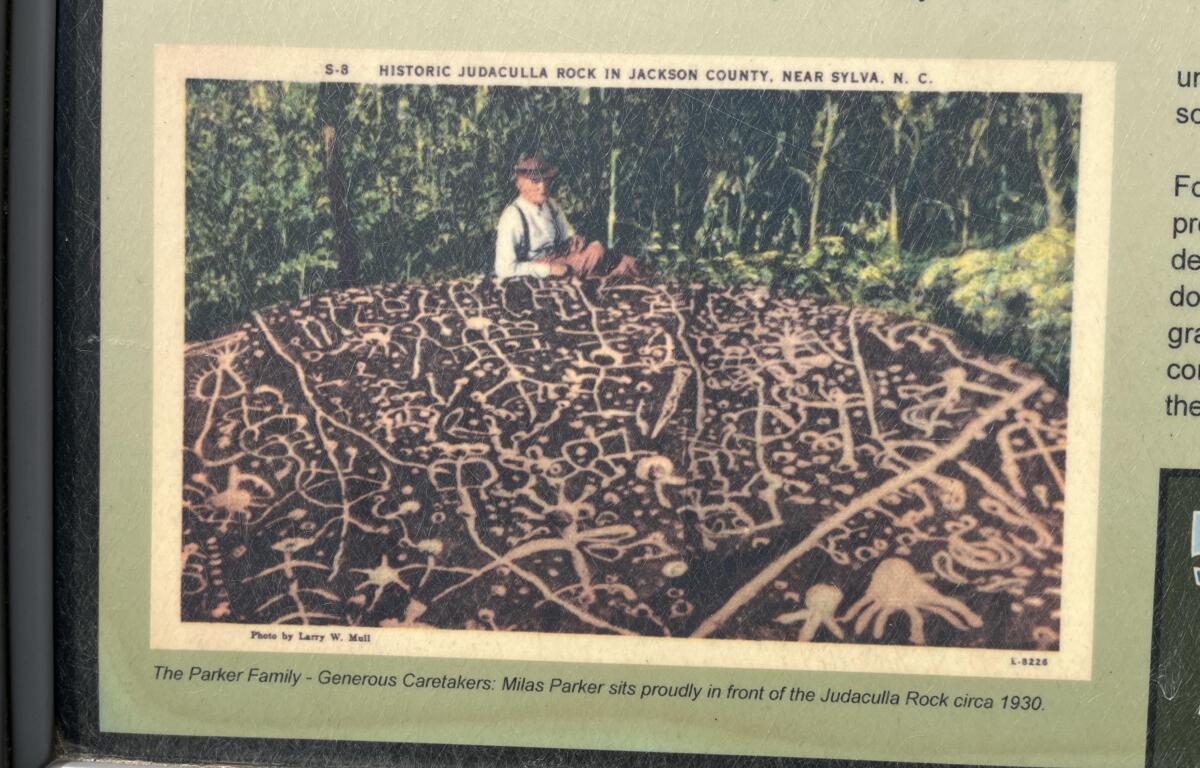

The soapstone boulder known as the Judaculla Rock is roughly 20 feet by 10 feet. How deep underground it goes is unknown. Approximately 1,548 designs cover the majority of its surface. According to the Blue Ridge Heritage Trail, the Judaculla Rock has “more [carvings] than any other known petroglyph boulder in the eastern United States.” At its base, there are bowl-making stations chiseled out of the stone.

Soapstone quarrying by native peoples in the immediate area “dates between the Late Archaic to Early Woodland” periods, roughly 3,000 – 200 B.C., according to Jackson County Recreation and Parks.

The State of North Carolina first recognized the significance of the site with a sign in 1938. Despite the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources (DNCR) calling the land “a 15-acre area that is an archaeological site of great significance,” only one acre is maintained by Jackson County. The Parker family, who have owned the land for generations, gave the stone to the county for preservation and research in 1959.

According to the Blue Ridge Heritage Trail, “In 2011, grandson Jerry Parker placed 107 acres of the family farm into a permanent conservation easement that protects the broader cultural site and preserves the undeveloped mountain experience for generations to come.” It is unclear if this easement will affect future research onsite. As of writing, a complete archeological survey of the area surrounding the Judaculla Rock has not been conducted.

Theories about the Judaculla Rock

Estimates on when the petroglyphs were chiseled vary wildly. Some researchers think the art dates to the time of Abraham. Others claim the etchings could have been carved as recently as the late eighteenth century. The spread of dates offered is almost 4,000 years. The DNCR claim a more recent date range of between 500 – 1700 A.D.

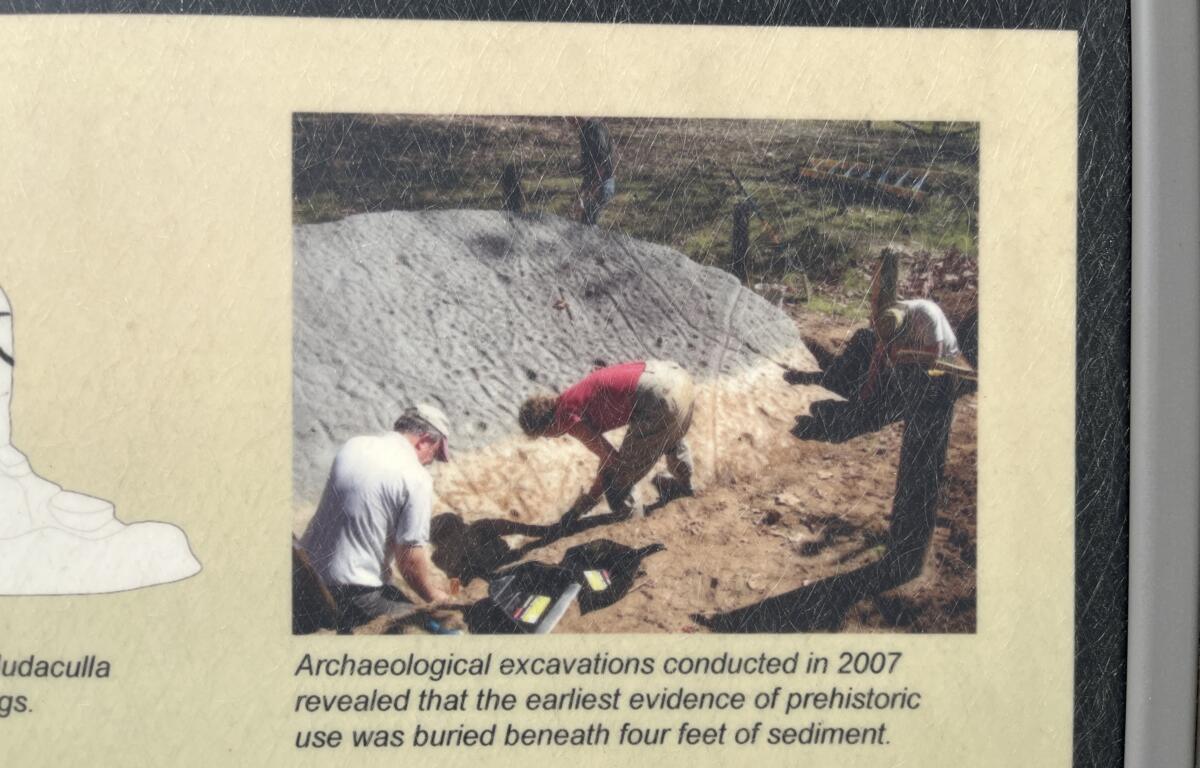

As explained by the plaques surrounding the boulder, the 2007 partial excavation in the immediate vicinity of the boulder unearthed some evidence that pointed to habitation around 3,000 years ago, digging down four feet to find it.

Rumors started by farmers around the turn of the twentieth century alleged two other petroglyphic boulders were in the area. One was lost to a cave collapse in a mining accident and the other is buried somewhere nearby the Judaculla Rock. Mooney was unsure if these rumors had merit.

The lack of significant scholarly research on the Judaculla Rock in recent decades has left the door wide open to conspiracy theorists who attempt to interpret the purpose of the carvings, when they were etched and if the Cherokee made them at all. Even if their theories are unfounded, bewilderment over the Judaculla Rock is warranted. The National Forest Service does not know what to make of the site, writing, “The meaning of the Judaculla petroglyphs remain a mystery to us.”

In the third season of the History Channel’s “America Unearthed” TV show, television personality Scott Wolter briefly inspects the Judaculla Rock in episode three. A local woman asks Wolter if it could have been of extraterrestrial creation, which he shoots down promptly. Others have made the same unfounded alien assertion.

Claiming to have conducted 15 years of research on the Judaculla petroglyphs, Hiram C. Wilburn came to the following conclusions, as published in the journal “Southern Indian Studies” in Volume IV in Oct. 1952. “Briefly, it is my belief that the rock is a… picture-map, of the battle of Tal-i-wa fought in the year 1755,” Wilburn wrote. “This was a hard fought battle between the Cherokee and their long-time enemy, the Creek Nation. The location was near the present town of Canton, Georgia. The Creeks were badly defeated and driven from the field.”

Multi-generational residents of the region recalled to Wilburn hearing stories of the rock being related to a battle the Cherokee fought “far to the south.” The homesteaders may have received that account from Mooney who made a similar claim 50 years prior.

“These same sources said that in the recollection of the previous generation, large groups of Cherokee Indians used to assemble at the rock, and remain for a day or two.” Wilburn records, “Solemn ceremonies or rituals would be carried on. The older members of the group with a long cane as a pointer would indicate different objects on the rock, and this would be followed by exclamations and animated chants. These visitations were likely as late as the 1880s and 1890s.”

Electromagnetic anomalies have allegedly been identified at the site. Considering the heavy mining in the region, it is possible a vein of some magnetized metal runs beneath the boulder, causing an anomaly. If true, this could potentially explain why the ancient Cherokee gravitated to the location and deemed it sacred.

Asheville Ghost Tours founder, Joshua P. Warren, weighed in with his own theory. “Warren made a connection to experiments he had conducted as a child. ‘The surface of the rock reminded me of the random ‘soup’ of microorganisms I would see as a kid when examining a drop of local creek water under a cheap microscope,’ he explains. ‘The resemblance was so uncanny that I wondered whether or not the ancient people who made those markings were depicting the same thing.’”

He theorized that the indigenous people could have used thin slices of mica with droplets of water to amplify the size of microscopic organisms.

A self-identified Creek Indian, Richard L. Thornton believes the Cherokee did not live in the Sylva region until 1745, thinking instead the Muskogee-Creek were inhabiting the area until expulsion by British forces in 1763. Furthermore, he conjects, “All of Judaculla’s symbols were used in the Apalache-Creek writing system.”

Intertwined with speculations about Spanish speaking Jews and Irish settlers in W.N.C. in the 1500’s, Thornton’s etymological thread leads him to suspect the Cherokee borrowed Tsul-ka-lu from the Muskogee-Creek’s “Suta-Kura.” “Judaculla means ‘Sky (over) Kura,” he expounded. “Kura was a Proto-Creek province in North Carolina. Their descendants are the Kulasee Creeks.” He interpreted Cullowhee, along with Curahee, Georgia, as corruptions of an “Archaic Irish word, Curaighhe, meaning “Place of the Kura (People).” The Kura Muskogee, he stated, assimilated into British society in Georgia or integrated with the Seminole.

Furthermore, Thornton believes Kura is a corruption itself of “Corra,” the name of an ancient group of red-haired and freckled people from “northern Ireland and southwestern Scotland.” He continued, “Apparently, what happened is that bands of immigrants from Northwestern Europe reached the gold, silver and gem-rich regions of the Southern Appalachians during the Bronze Age.”

Conclusions about the Judaculla Rock

Not knowing who made the markings naturally makes them more difficult to decipher. A contemporary example is a preschooler’s art. When a boy takes his drawing to his mother, she instinctually knows that the stick figures are members of their family. If the child hangs the same drawing in the Asheville Art Museum, nobody will have any clue who the figures are. Without the knowledge of the artists, their society and symbols, we are like spectators in the gallery scratching our heads at the indecipherable representations. And yes, there are multiple stick figures on the Judaculla Rock.

What most authors can agree on is that the petroglyphs depict some kind of map. Defining what the map represents and when it was made are where the conflicts arise. It does not help that, as most researchers agree, the petroglyphs do not appear to have been made all at the same time, displaying differing amounts of weathering.

The Cherokee legend of Judaculla creating the petroglyphs is a clue in itself, suggesting perhaps one of two things, both of which support an earlier date for the etchings. Either the Cherokee did not make the designs and created a story about a giant to explain what they found, or they had forgotten that they made them and for what purpose, creating the tall tale to fill in the gaps in their collective memory. Even if you grant that a seven-foot-tall giant was involved with its creation, he could not be responsible for all the depictions due to their differing ages.

There is also a “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” situation going on with the Judaculla Rock. Given that there is a seven-fingered hand carved into the soapstone, is it possible that when the Cherokee found the petroglyphs, they created the giant to explain the handprint? Or did they carve the seven-fingered hand to connect the boulder to their pre-existing narrative of the slant-eyed Judaculla?

A few of the theories on the Judaculla Rock can be easily thrown out. Due to the range of dates being several hundred years, the carvings could not have depicted a Cherokee battle in the late eighteenth century as Mooney and Wilburn proposed. Those battles happened far too recently. Extraterrestrials also make little sense. Similar petroglyphs are found throughout the Southern Appalachians that are not attributed to otherworldly sources.

The most compelling theory is the double map approach. Some posit there are two maps superimposed on top of each other, one of the heavens, and the other of the earth. This theory explains many of the peculiarities with the petroglyphs. The random dots could be stars, the abstract shapes could be constellations, and the detailed landmarks could be villages and other key locations. Even the differing dates are explainable. Perhaps the two maps were made at different times. New features could have been added to the terrestrial map as new villages were formed. But this is surely not the only possible or only logical explanation.

Attempts to decode the petroglyphs are becoming progressively harder as corrosion overtakes the artwork. The same properties of the boulder that made it easy to carve make it susceptible to erosion. Vandals and the weather have been causing losses to the Judaculla Rock. It has become difficult to distinguish between the petroglyphs and natural contours in the stone.

Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2013, you would think long lines of anxious visitors would be the norm. But what should be a national landmark with regular archeological investigations sits alone in a field. Hardly anyone visits, research has not been done on it since 2007 and thousands of Western Carolina University students live within walking distance yet have never seen or heard about the Judaculla Rock.

Visitation of the Judaculla Rock is permitted daily during daylight hours at 552 Judaculla Rock Rd., Cullowhee, N.C. No admittance fee is required. Guests should avoid touching the petroglyphs to prevent unnecessary erosion.

Do you have a bizarre, weird or extraordinary story about Western North Carolina? Let us know by emailing jvander-weide@avlradio.com. Your tall tale could be the next Strangeville story.

Learn more about W.N.C.’s strange history with one of these articles: