EDITOR’S NOTE: Everyone has a story — some more well-known than others. Across Western North Carolina, so much history is buried below the surface. Six feet under. With this series, we introduce you to some of the people who have left marks big and small on this special place we call home.

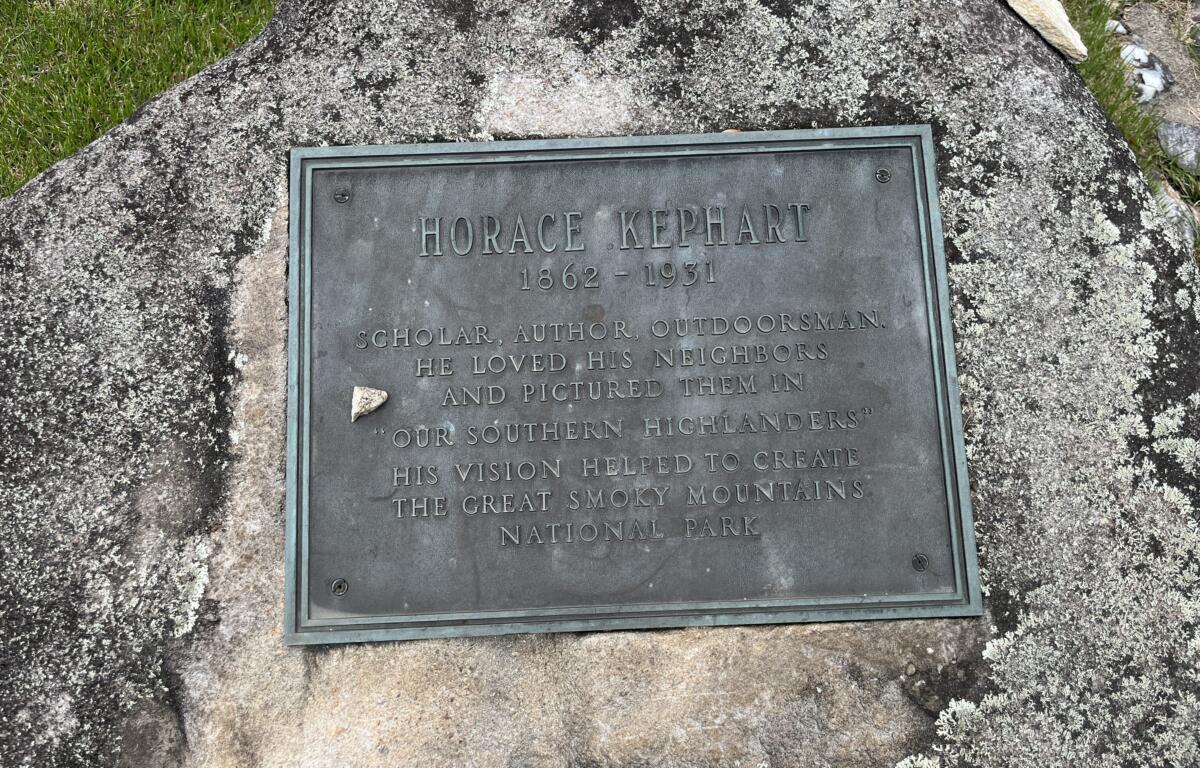

Author of “Our Southern Highlanders” and advocate for the creation of Great Smoky Mountain National Park, Horace Sowers Kephart (1862-1931) became the permanent scholar on both camping and the people of rural Western North Carolina before his tragic death in a car accident in 1931.

Life before the mountains called

Horace Sowers Kephart was born on Sep. 8, 1862, in East Salem, Pennsylvania to Swiss immigrants Isaiah L. and Mary Elizabeth Kephart. His father was a teacher and clergyman. As a five-year-old, the family moved to Iowa, hoping to begin anew as farmers. The endeavor lasted a decade before the family returned to Pennsylvania.

After graduate school, Kephart spent some time studying and collecting works across Europe. Returning to the U.S., he married Laura Mack in 1887. The couple moved several times as Kephart found work as a librarian in some of the most elite universities in the country. Settling down at the St. Louis Mercantile Library in 1890, he became a leading scholar on the Western United States.

Kephart’s career fell apart after taking to drinking and embarking on extended journeys through the Ozarks. Well into his midlife, he was pressured to resign from the Mercantile. Having a nervous breakdown, Kephart’s father went down to take the broken man back to Dayton, Ohio in 1904. This move would estrange Kephart from his wife and six children for the rest of his life. After a few months of recovery, Kephart took the train to Dillsboro, N.C., getting off in early August. He set up “Camp Toco” on Dicks Creek for the next several months before retreating into an abandoned cabin on Hazel Creek for the winter in a remote region north of Proctor.

Affair with Western North Carolina

Kephart delighted in the clan-like and suspicious-of-tourists tendencies of the mountaineers, . “He wanted to go to a place of which nothing was known,” the Asheville Citizen reported on April 3, 1931. “He wanted solitude.”

Scribbling down the curious stories he heard and the mannerisms of the people he met, Kephart became the sole authority on the Southern Appalachian “mountaineers,” as he would call them. Kephart’s work, specifically “Our Southern Highlanders” (1913) romanticized the lives of the moonshiners and woodsmen, despite the torn socks and overalls covered in patches they wore.

In W.N.C., Kephart also attained the rank of permanent scholar on camping in America, writing for most of the major outdoor magazines during a resurgence of interest in the great outdoors. Kephart inspired the next generation of outdoorsmen as the Boy Scouts of America was being founded.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park

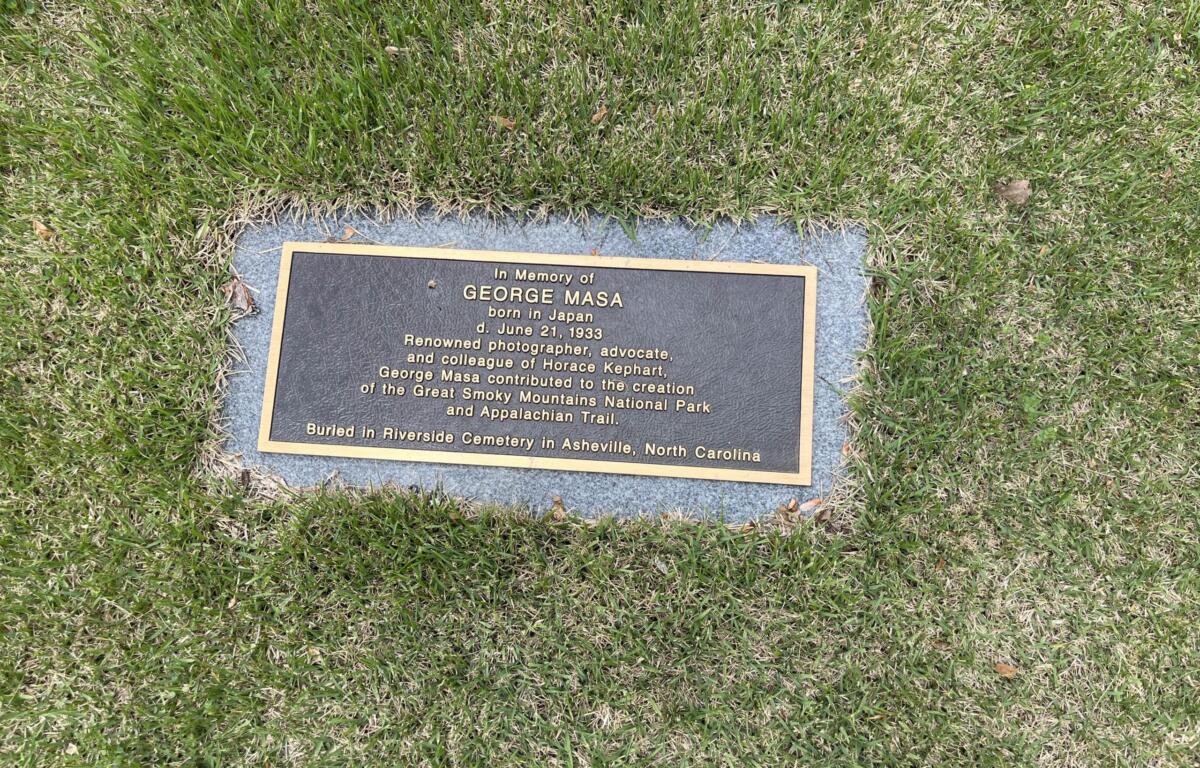

It is quite difficult to understate the contributions of Kephart and his dear friend George Masa, a photographer from Asheville, in the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP). Kephart fought ardently for the land to become a National Park rather than a member of the National Forest Service. This effort paid off, preventing the mountains from logging indefinitely.

“When Representative Zebulon Weaver introduced a bill in Congress for the creation of the national park, it was accompanied by a letter from Mr. Kephart,” the Asheville Citizen reported on April 3, 1931. Furthermore, the Citizen wrote, GSMNP “probably wouldn’t be without the impetus furnished by the sincere and laborious effort of Horace Kephart.” A week later, on April 12, the newspaper called the writer the “Apostle Of Great Smokies.”

Beyond the work he did for GSMNP, Kephart assisted in planning the section of the Appalachian Trail where it crosses through Western North Carolina.

Two friends reunited at last

As petitioned by the residents of Bryson City to the National Geographic Society, the 6,217-foot Mount Kephart was the first mountain to be named for living person. On the peak’s shoulder is Masa Knob.

Horace Sowers Kephart died in a car crash on April 2, 1931, near Ela, N.C. with Georgian author Fiswoode Tarelton. Distracted by a passing car’s headlights, the author’s cab driver narrowly survived the wreck. Kephart was thrown 40 feet from the vehicle and died on impact at the age of 68.

George Masa died bankrupt, unable to pay for his wish to be buried next to his friend, Kephart. In 2023, a century after Masa’s death, a group known as “Project Reunite” secured the funds to put a plaque next to Kephart’s grave commemorating Masa. A plaque for Kephart’s estranged wife, Laura, was also added.

If you enjoyed this article, consider reading one of these Tombstone Tales: