EDITOR’S NOTE: Western North Carolina is weird – and it always has been. From Cherokee myths to Bigfoot and alien encounters, the Blue Ridge Mountains host the quirky and bizarre from past and present. We would not have it any other way, and neither would you. Join us in unfolding the histories and unraveling the mysteries of this strange land we call home.

___

Due to the harsh Southern Appalachian terrain, fallout of the American Civil War and corruption in the railway authority, Western North Carolina was one of the last regions in the contiguous United States to be reached by rail. When the train finally arrived, an economic boom ensued. Travel to the cities and material exports finally became viable. To honor the legacy of these crucial railways, a massive model train set has been educating and entertaining guests in Hendersonville for 33 years.

History of the Railroad

1879 is perhaps one of the most influential years in the history of W.N.C. For the first time, chains chugged along newly minted railways into Asheville and Hendersonville, each surmounting their own challenges. The Asheville route had to cross the continental divide and Hendersonville’s rose above the Saluda Mountain Grade.

The Saluda Grade is an architectural marvel, even by today’s standards. While not currently in operation, the rails climb more than 600 feet in less than three miles, making it the steepest railway section in the United States. When the first train attempted to make the climb, it required two steam engines to summit the grade.

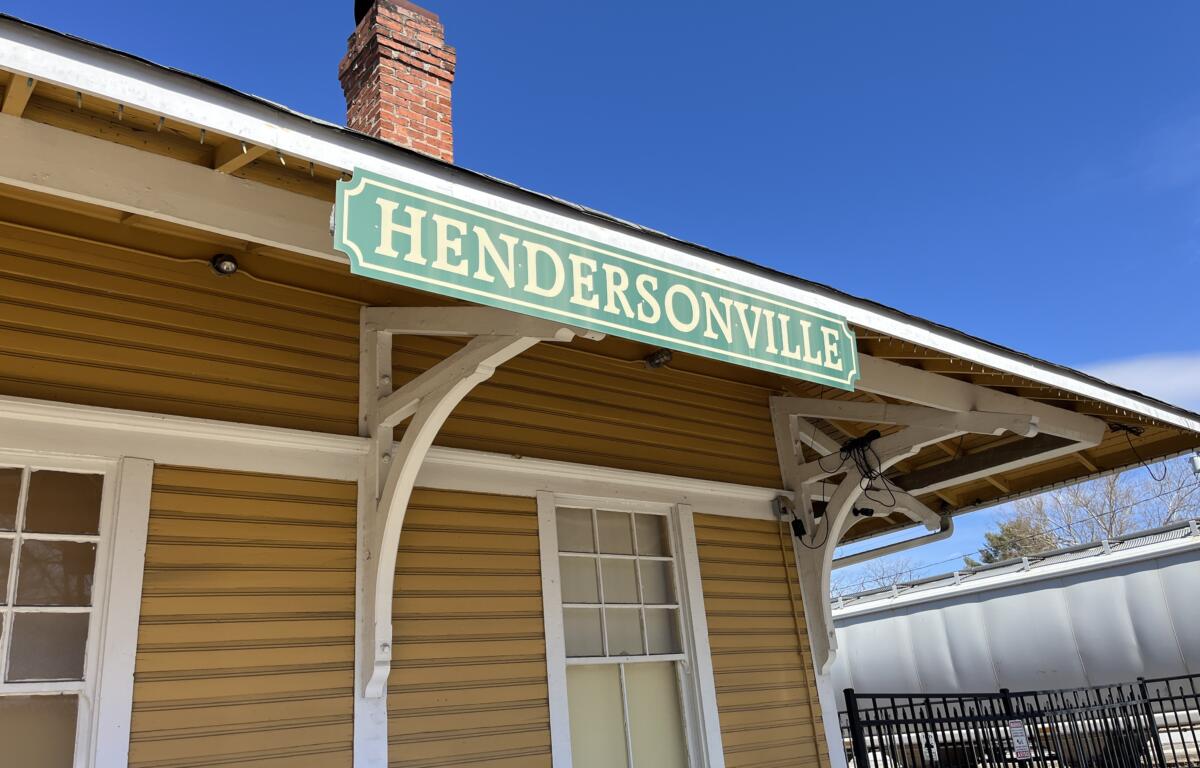

The train rolled into Hendersonville to much fanfare in June 1879. It stopped at a newly constructed rail station. The station was cramped, causing the railway authorities to replace it in 1902 with the existing building the museum uses today. Several additions were made to the structure over the years, primarily for the passenger segregation.

If you are from outside the city, you may notice similarities between your town’s train station and Hendersonville’s. This is no coincidence. Cost saving measures included reusing architectural designs. Hendersonville’s first depot was a copy of Saluda’s, and their second is nearly identical to Black Mountain and Old Fort’s depots.

Six passenger trains daily stopped in Hendersonville during the station’s heyday, connecting riders as far north as Cincinnati, Ohio, and as far south as Charleston, S.C.

Passenger service ended at Hendersonville’s stop in 1968. As a public, yet derelict building, the Apple Valley Museum Railroad Club explains, the depot “became the unofficial unemployment office for the City of Hendersonville. Men would stand and wait under this pavilion for farmers, builders, and other employers to drive by and hire several men for a day’s work. Over time this practice became a problem for the city and the pavilion was sawed off and removed in 1972 to end this public nuisance.”

Norfolk Southern, the owners of the line through Hendersonville, attempted to raze the historic depot in the latter half of the 1980’s. Citizens were incensed by the proposition, successfully lobbying the city’s Parks and Recreation Department to save it from the wrecking ball. Volunteers revamped the structure and fund raisers paid for the material costs.

The railway owners continued to transport cargo through Hendersonville until 2002. In 2014, Norfolk Southern’s abandoned Hendersonville line was sold to the Blue Ridge Southern Railroad.

History of the Museum

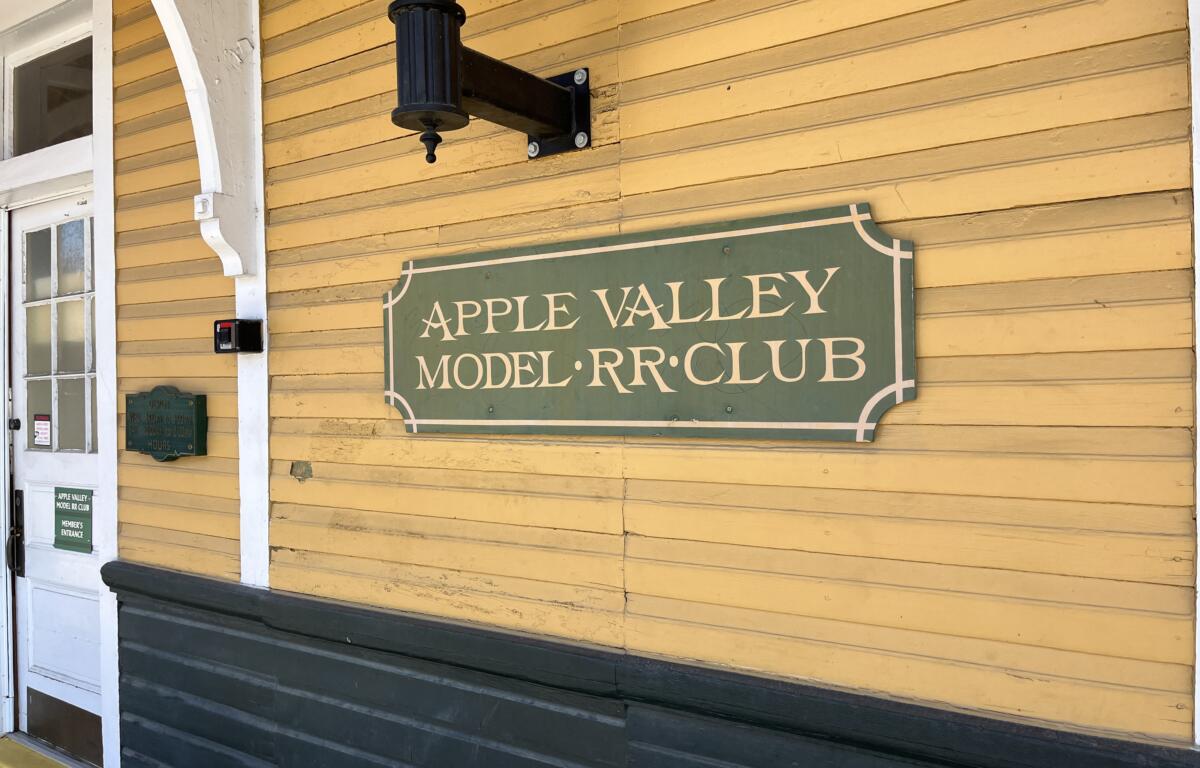

In 1992, the City of Hendersonville began leasing the depot to the Apple Valley Model Railroad Club to use for their museum. Recognized as a historic landmark in 2000, the building is protected from future attempts to remove it.

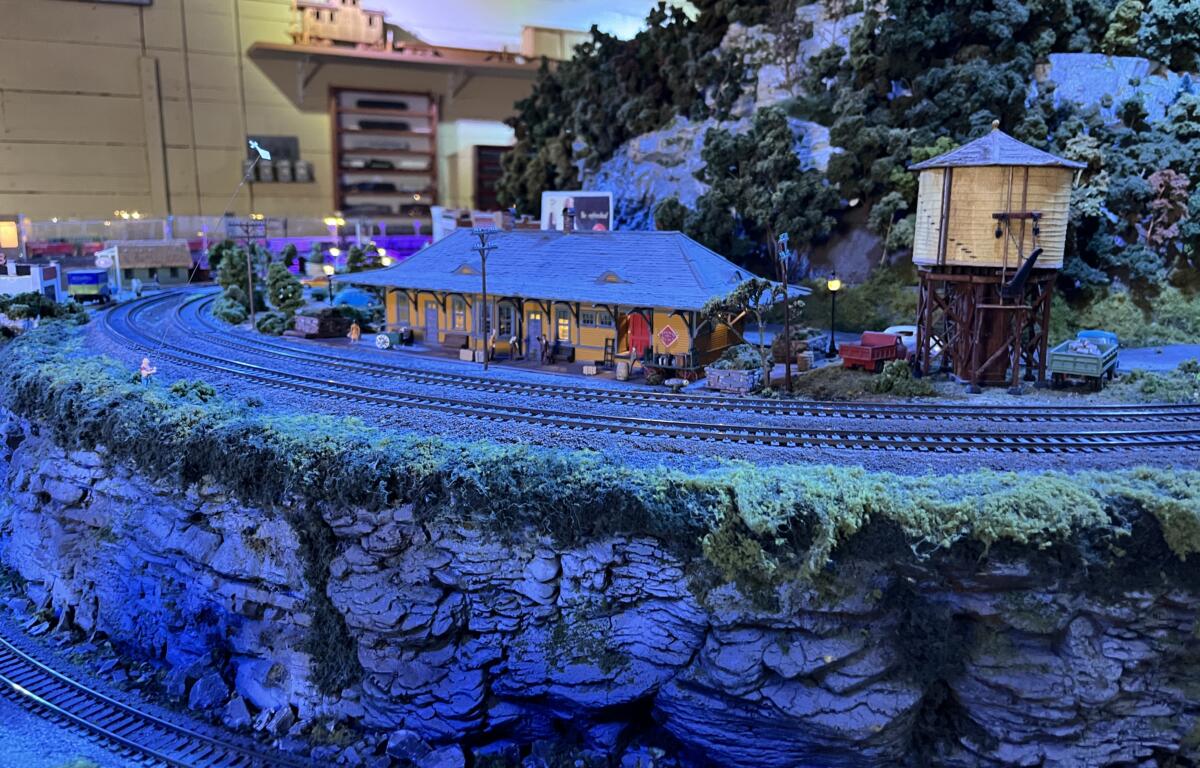

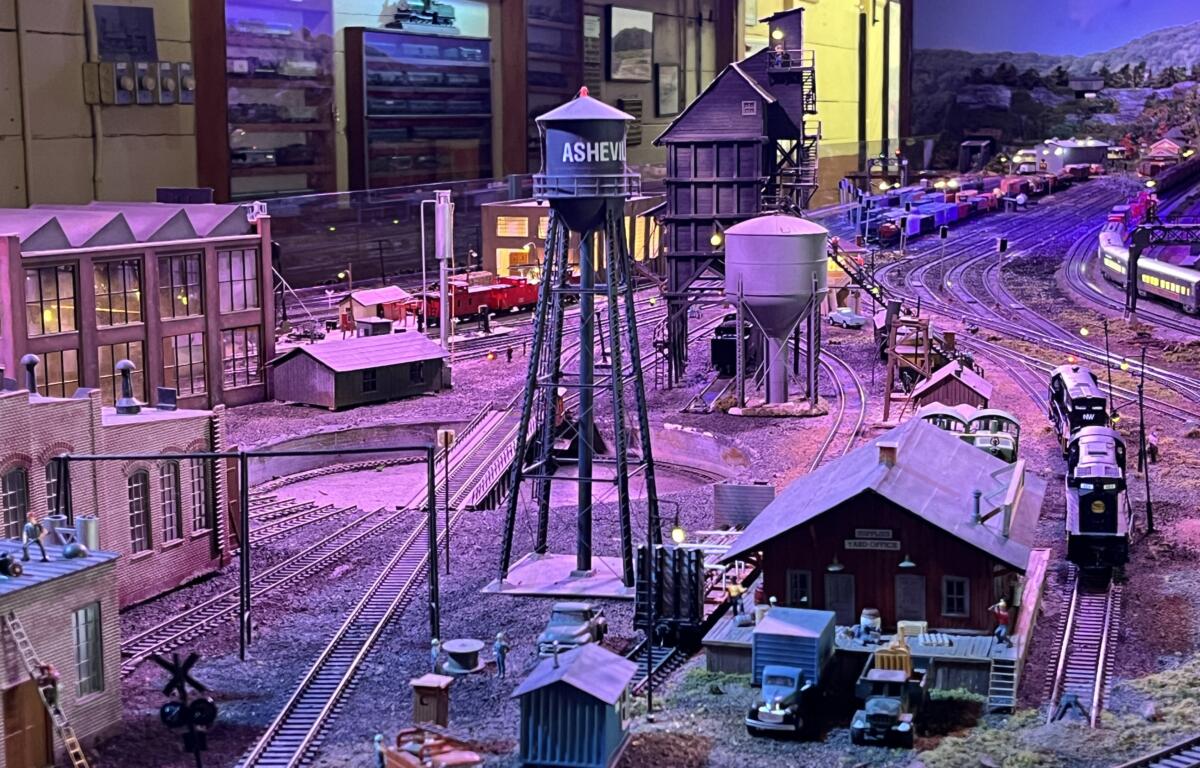

Filled with all manner of railroad historical artifacts, the museum inside of Hendersonville’s restored depot doubles as both education and entertainment. On the educational side, members of the club explain the history of the W.N.C. railroads. As for the entertainment, there are three tracks of model trains to observe winding around the carefully manicured dioramas.

The primary indoor track is built in HO scale, which is a 1:87 ratio to real trains. It features over 1800 feet of track spanning multiple rooms. Along the route are the towns that occupy the real life line, towns like Spartanburg, Saluda, Black Mountain, Asheville and Hendersonville.

Next to the primary track is a Thomas the Tank Engine track for children to operate. Also built in HO scale, the tv show themed route is a load of fun for littles.

Outside the museum are a G scale model laid out across a 12 by 60-foot area and a decommissioned caboose you can climb inside of. The outdoor model, while occupying a smaller area, has much larger engines at a 1:25 ratio. It displays what logging operations in W.N.C. were like.

You can visit the museum at 650 Maple Avenue, Hendersonville, N.C. Admission and parking are free for visitors. Doors are open from 1 – 3 p.m. on Wednesdays and 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on Saturdays. Group tours for 10 or more people are offered if requested in advance. As a non-profit, the museum accepts donations to continue their operations.

Do you have a bizarre, weird or extraordinary story about Western North Carolina? Let us know by emailing jvander-weide@avlradio.com. Your tall tale could be the next Strangeville story.

Learn more about the strange history of W.N.C. with one of these articles: