EDITOR’S NOTE: Western North Carolina is weird – and it always has been. From Cherokee myths to Bigfoot and alien encounters, the Blue Ridge Mountains host the quirky and bizarre from past and present. We would not have it any other way, and neither would you. Join us in unfolding the histories and unraveling the mysteries of this strange land we call home.

___

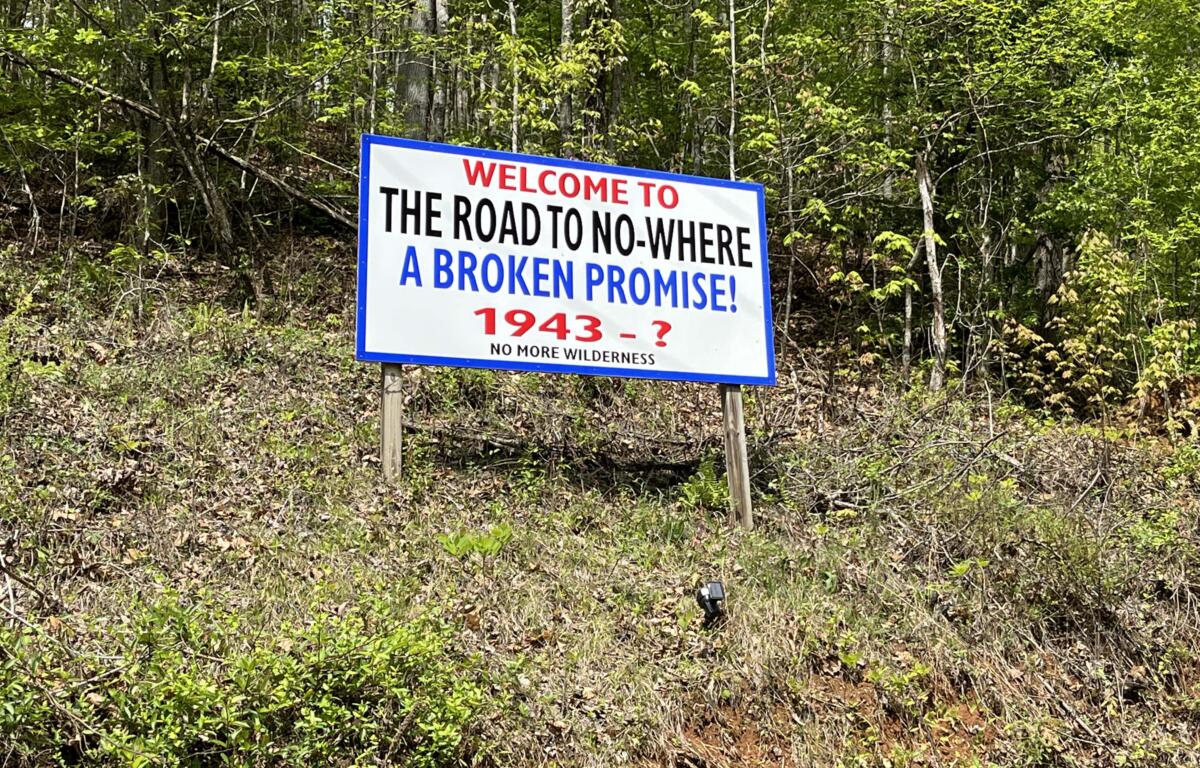

Driving north out of Bryson City yields a peculiar result. After passing Swain County High School and various private residences, two opposing signs greet visitors. On the right, the official plaque announcing you are entering Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP). The other sign reads, “Welcome to the Road to No-Where. A Broken Promise! 1943 – ?”

Passing these signs and continuing for several miles, you will reach a quarter mile long tunnel leading to nothing. The story of this mysterious monument has irked Swain County for more than 80 years now.

A broken promise

As the American war machine revved to life in the early 1940’s, energy needs skyrocketed. In the Southern Appalachians, electricity was needed to power steel plants and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory where the Manhattan Project was conducted. To generate more power, the Tennessee Valley Authority dammed the Little Tennessee River. The 480-foot-tall dam is the largest east of the Rockies, creating the 16 square mile Fontana Lake.

Swallowing up entire communities of valley dwellers, Fontana Lake drowned several settlements. The U.S. Department of the Interior promised the evicted residents to build a new highway to reach their ancestral cemeteries. Three decades passed of bureaucrats dragging their feet, only building six and a half miles of the more than 30 miles pledged. Due to the environmental concern of unearthing the region’s pyrite, which could have caused acidic runoff into waterways, the highway was canceled in the 1970’s.

Unsurprisingly, Swain County was furious. Over the following decades, they fought for the road to be built. Ultimately, the federal government would not budge, forcing the county to settle for $52 million in damages for breach of contract. The settlement funds remain in the trust of the N.C. Department of State Treasurer. Each year, Swain County is paid the interest on the money which is used for public services.

Making the best of a bad situation

Just before the highway building halted, a 1,200-foot-long tunnel was constructed. Leading to nowhere, it sits abandoned as a constant reminder to the residents of Swain County of the broken promise.

Seeking to make lemonade with the lemons the U.S. Department of the Interior left them, Bryson City has turned to using the tunnel as tourist attraction. It serves as a gateway to hiking and horseback trails for visitors of the southeast section of GSMNP.

Each summer, National Park Service rangers ferry descendants of the submerged communities across Fontana Lake to visit their ancestral homelands. On these “Descendant Days,” some say they can see the tallest buildings of the once booming lumber town of Proctor beneath the waves. Hazel Creek is also lost beneath the water, once home to Horace Kephart, the man perhaps most responsible for the creation of GSMNP.

You can visit the Road to Nowhere and the forgotten tunnel during daylight hours any day of the week at the terminus of Lakeview Drive near Bryson City. An overlook for Fontana Lake is also accessible on the road. Repaved in 2023 with funds from the Great American Outdoors Act, it is a smooth drive up to the tunnel.

On very sunny days, the tunnel is traversable without additional lighting. In most other circumstances, a flashlight is required to avoid tripping on piles of dirt and leaves. Graffiti artists have tagged the entire length of the tunnel on both walls.

Trails surround the tunnel if you want to make a day out of the trip. Particularly adventurous tourists can hike the multi-day Lakeside Trail which follows the route where the highway should have been built.