Editor’s Note: Western North Carolina is rich with untold stories—many resting quietly in local cemeteries. In this Tombstone Tales series, we explore the lives of people from our region’s past whose legacies, whether widely known or nearly forgotten, helped shape the place we call home.

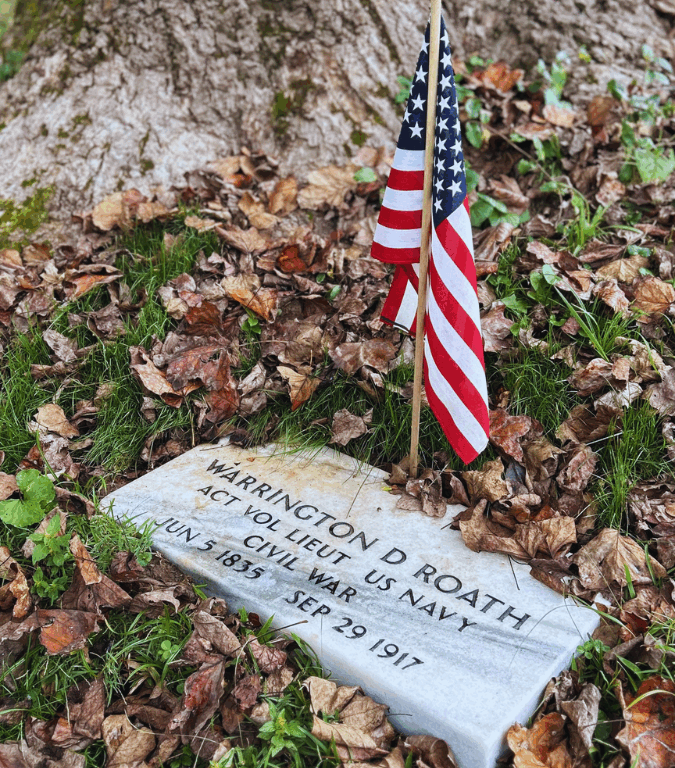

ASHEVILLE, N.C. — On a quiet hill in Riverside Cemetery, a single white military headstone stands apart from the family plots and the long rows of veterans in another section of the cemetery. The marker is simple: Warrington D. Roath, Act Vol Lieut U.S. Navy Civil War.

There are no family names nearby, only the distant hum of the city. This peaceful corner of Riverside is where a sailor from Connecticut, who once crossed oceans and fought in two wars, found his final rest.

Capt. Warrington D. Roath’s story drifts between honor, heartbreak and mystery.

Born in Norwich, Connecticut, in 1835, he came of age as the country edged toward civil war. When President Abraham Lincoln called for troops, Roath joined the Second Connecticut Volunteers and fought in the first battle of Manassas. He later transferred to the Navy, commanding gunboats under Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter during the Civil War and later serving in the Spanish-American War. He entertained friends with stories of having survived 29 engagements without ever being wounded.

His naval career carried him around the world eight times. He stood beside Adm. George Dewey during a bombardment and served off the Cuban coast before retiring after decades at sea. In the early 1900s, the veteran who had lived his life on water chose to settle among the mountains of Asheville.

Neighbors in the Woolsey community remembered him as proud but friendly. A man who kept to a sailor’s routine and often wore his uniform around town. He was known simply as “the Captain.” Children stopped to listen when he spoke of faraway ports and narrow escapes.

In 1911, on the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Manassas, the Asheville Citizen interviewed him about that first Civil War fight. Roath told the reporter he still remembered the roar of cannon and the whine of the minie ball. He said he hoped to find a Confederate veteran who had fought that same day so they could shake hands in friendship half a century later, but none could be found in Asheville. The moment of reconciliation he sought reflected the spirit of peace many veterans longed for as the war’s memories faded into history.

By 1917, age and illness had confined him to his small home. Friends knew he had a wife and daughter somewhere out west, but he never spoke of them. When they realized he was dying, they begged him to give their address so they could be notified. He refused. Even as his strength faded, he guarded that secret.

After his death, his friends sent telegrams across the country searching for his family. One reached Col. Walker Taylor, collector of the port of Wilmington, who confirmed that Roath’s government pension had long been sent each month to his wife, Louise, in San Francisco. Despite their separation of 13 years, he had continued to support her.

Census records show that Louise listed herself as widowed, though she knew he was alive. For women who lived through war and long separations, widowhood on paper was often simpler than explaining abandonment or the breakdown of a marriage that led to separation.

Days after his death, a telegram arrived in Asheville addressed to Postmaster Owen Gudger. It came from LouiseRoath. “Kindly take charge of Captain W. D. Roath’s remains, bury in Asheville”.

Her message ensured his wishes were carried out.

Friends arranged the funeral. Dressed in full naval uniform, his body was draped in the American flag and buried on a quiet hill in Riverside Cemetery.

For years, his grave was unmarked.

More than a century later, Capt. Roath’s story reached a new generation. On July 31, 2025, members of the Virginia Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States placed an updated government-issued headstone on his grave, honoring him as an “Original Companion” of the Loyal Legion. Founded in 1865 by Union officers, the organization continues to preserve the legacy of those who served the Union cause. The ceremony reconnected Roath’s memory to that lineage, ensuring his service would not fade from history.

The new stone is a quiet testament to the life of a man who crossed oceans, survived two wars and carried his secrets to the grave. Whatever divided him from his family, his final wish was fulfilled.

Capt. Warrington D. Roath rests where he chose, far from the sea in the mountains of western North Carolina, beneath the flag he served.

Riverside Cemetery, Asheville, North Carolina

-

Tombstone Tales: Flat Rock’s Slaves and Freedmen Memorial

Beneath a quiet stand of trees near Flat Rock’s oldest Episcopal church, a granite cross rises above a hillside of small white markers. It is one of the few memorials dedicated to enslaved and freed African Americans in Western North Carolina.