EDITOR’S NOTE: Everyone has a story — some more well-known than others. Across Western North Carolina, so much history is buried below the surface. Six feet under. With this series, we introduce you to some of the people who have left marks big and small on this special place we call home.

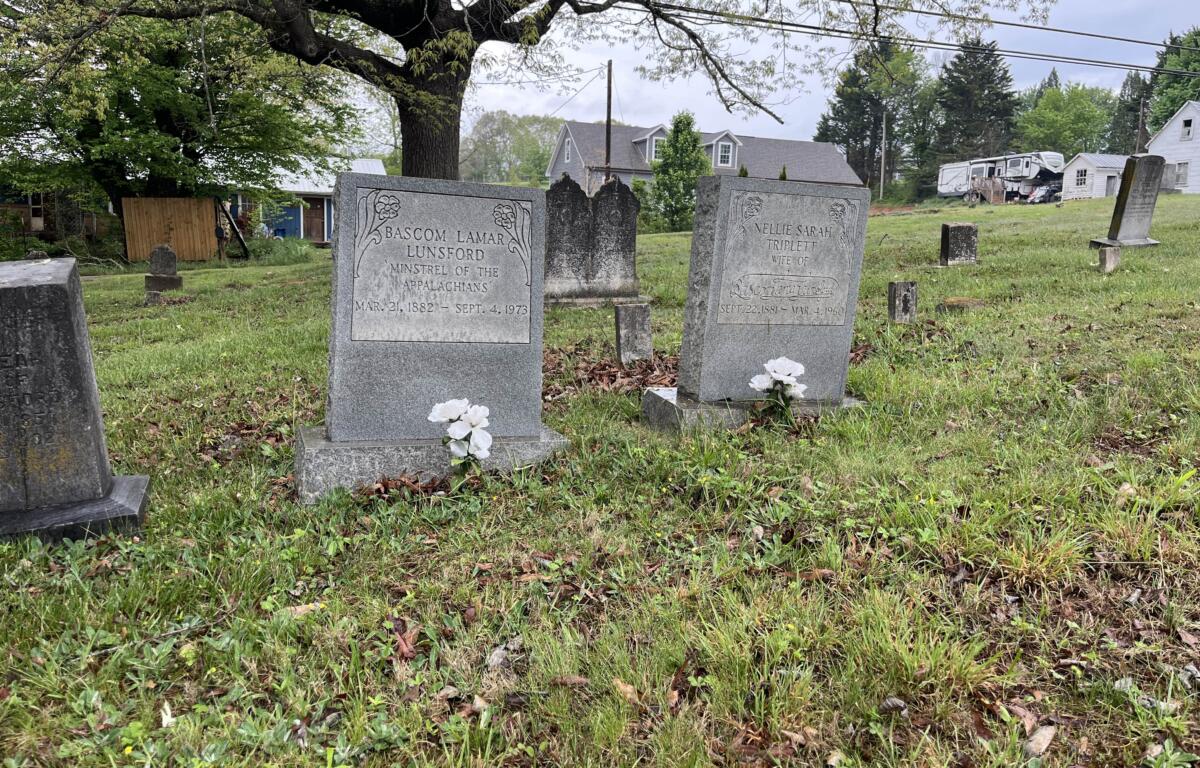

Defined as the “preeminent collector of Appalachian folk ballads, showman, buck dancer, and folk festival founder” by the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, Bascom Lamar Lunsford (1882-1973) is one of, if not the most important figure in the revitalization of Southern Appalachia mountain culture. His cultivation of folklore, folk songs and folk dancing shifted national views on the folk arts. Lunsford created the first and longest running folk festival in the United States of America.

Picking as a boy

A historical marker at Mars Hill University alerts visitors, students and faculty that Bascom Lamar Lunsford “Was born here.” Engraved in the most literal sense, the future world-famous folk musician and preservationist was born on the campus to a professor and his wife.

Lunsford was born to James and Laurtie Lunsford on March 21, 1882. “His father was a Confederate veteran from East Tennessee, and his mother came from a Unionist family from Buncombe and Madison Counties,” reported Blue Ridge Heritage. Music was imbued in Lunsford’s nature from birth. “His mother was a ballad singer, and her family included fiddlers and other musicians. When Bascom and his brother Blackwell were children, they learned to play the fiddle, and then as teenagers took up the banjo, which would become Lunsford’s primary instrument.”

Those early instruments the brothers played caused more than a few headaches. The Lunsford brothers’ handmade fiddles from cigar boxes. Apparently making quite a racket, John Parris wrote that the boys played so long that “their neighbors said surely the Lunsford boys had caught some young crows,” as written in the Sep. 5, 1973, edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times. After the incident, their father relented, purchasing them real banjos and violins.

Mars Hill University explains the musical bones ran further back in the family than Lunsford’s mother, writing, “his maternal great-uncle Os Deaver was a renowned fiddle player and his mother sang ballads.”

In his youth, Lunsford was educated in one room schoolhouses, and later on at Camp Academy in Leicester. In 1906, he married his childhood sweetheart, Nellie Triplett. The couple had seven children together before Nellie’s death.

Early career attempts

“As a grown man, Lunsford worked in many different professions over the years,” wrote Blue Ridge Heritage. “He was a fruit tree and honey salesman, lawyer, publisher, teacher, and reading clerk in the North Carolina House of Representatives.”

“Bascom re-enrolled at Rutherford College and after graduating in 1909,” explains the Blue Ridge Music Hall of Fame, of which Lunsford is a member. “[He] enrolled in the law program at Trinity College, which later became Duke University. He passed the Bar exam and was licensed in 1913.” Degree in hand, Lunsford returned to his alma mater to teach students at Rutherford College, although this career was short-lived.

It was at Rutherford that Lunsford found his true passion. First asked to lecture informally on folk lore and play his banjo, the folklorist found his knack for wooing crowds with mountain tunes and stories.

As an inheritance, Nellie Lunsford received 140 acres in Leicester along South Turkey Creek. In 1925, Bascom and Nellie moved there, where he would later receive the nickname “the Squire of Turkey Creek.”

“The Minstrel of the Appalachians”

Calling himself “the Minstrel of the Appalachians,” Lunsford “set out to make himself a one-man repository of the old tunes and began a crusade to awaken the pride of his own people in their traditional music,” explained the Citizen-Times in his obituary.

By 1922, Lunsford was appearing on records. Estimates on exactly how many songs he recorded throughout his career vary from 300 to 3,000. In one week in 1959, he reportedly recorded 350 songs for the Library of Congress, all from memory. Recording sessions for the Columbia University Library archives and for commercial purposes were also undertaken, likely pushing Lunsford’s total records into the 500 plus range on the low end. His voice and picking span all formats from the era – cylinders, aluminum discs and vinyl.

“Mountain Dew” is likely his most famous song, one which Lunsford claimed to have penned himself. It has been rerecorded by the likes of The Stanley Brothers, Doc Watson, Grandpa Jones and Willie Nelson.

If you asked Lunsford, “What was your greatest honor?” he probably would have recalled a day in 1939. Summoned by President Roosevelt, Lunsford travelled to Washington D.C., bringing along with him a few other balladeers including Samantha Bumgarner. Performing before the president and the monarchs of the United Kingdom, the Citizen-Times reported on Sep. 5, 1973, “the king smiled, and the queen patted her foot.”

Mountain Dance and Folk Festival

As Asheville was booming, attempting to grow into the “Chicago of the South,” the Chamber of Commerce approached Lunsford in 1928 with an idea. In addition to the existing Rhododendron Festival, his group of mountain singing friends could play music and dance for crowds, adding another layer of entertainment to the Asheville tradition.

After two years appearing at the Rhododendron Festival, Lunsford spun his show off into the first American folk festival called the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival. Nearly a century later, the show continues to impress Ashevillians and others who descend on the mountain town each August for the event.

Lunsford supposedly gave a young Pete Seeger his first banjo lesson at the Asheville festival in 1935, inadvertently setting off a chain of events that led to Bob Dylan’s infamous electric guitar stampede at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965.

With his success in Asheville, Lunsford spread the concept to cities and colleges around the country, bringing his vision for respectable folk traditions to a broader audience. What started on a 10-foot by 10-foot platform in Pack Square became a national movement.

Problematic political record

Lunsford was notable in the local political landscape as a campaign manager. In 1952, he mounted a campaign of his own, aiming for the N.C. State House of Representatives seat for Buncombe County. A stain on his record, Lunsford was a notable member of the southern Democratic Party, often referred to as the “Dixiecrats,” during the Civil Rights era.

“’Mountain music’ and square dance traditions came to be associated with European Americans; spirituals, blues, and jazz with African Americans,” as Mars Hill University explained. “Lunsford’s collections and festivals, which were undertaken in the Jim Crow South, clearly reflected these divisions and predominantly (though not exclusively) featured white people.”

An example of this behavior is Lunsford’s treatment of “Swannanoa Tunnel.” Erroneously believing the song to have been written by white residents of Swannanoa, he sung it without many of the original lyrics, although it is not clear if he was aware of the song’s origins.

In truth, the ballad is a hammer song, chanted by prisoner “chain gangs” between hammer swings while mining tunnels. While chipping through what would soon become the 1800-foot-long Swannanoa Tunnel for the W.N.C. Railroad, a cave-in killed several members of the predominately black workers. Prison guards buried them in an unmarked mass grave near the tunnel in Black Mountain.

Lunsford’s lingering legacy

Picking and singing were Lunsford’s great passions, continuing to practice well into his elderly years. Only after his second stroke did he lay down the banjo, physically impaired from playing anymore.

A few months before his death, Lunsford won the W.N.C. Historical Association Achievement Award in 1973 “for his many years of preserving mountain folklore and music.”

Shortly after appearing at his forty-sixth Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, the 91-year-old Bascom Lamar Lunsford died on Sep. 4, 1973, in Asheville. A funeral was held for the late festival organizer on Sep. 6, 1973, in the chapel at Groce Funeral Home. He was buried in the Leichester Episcopal Church Yard alongside his first wife, Nellie.

Lunsford’s legacy is not found in the songs he recorded. Few of them are available on the Library of Congress’ website. He is remembered for reviving mountain pride, restoring to the Appalachians their ability sing and dance in their own unique way without the scorn of the elites. His work was furthered by John Parris’ series “Roaming the Mountains.” Parris did to reporting what Lunsford had done for song.

Do you know of someone buried in Western North Carolina with an intriguing or uplifting story? Let us know by sending us an email.

Interested in learning more about the people who made W.N.C. what it is? Check out these articles: