EDITOR’S NOTE: Everyone has a story — some more well-known than others. Across Western North Carolina, so much history is buried below the surface. Six feet under. With this series, we introduce you to some of the people who have left marks big and small on this special place we call home.

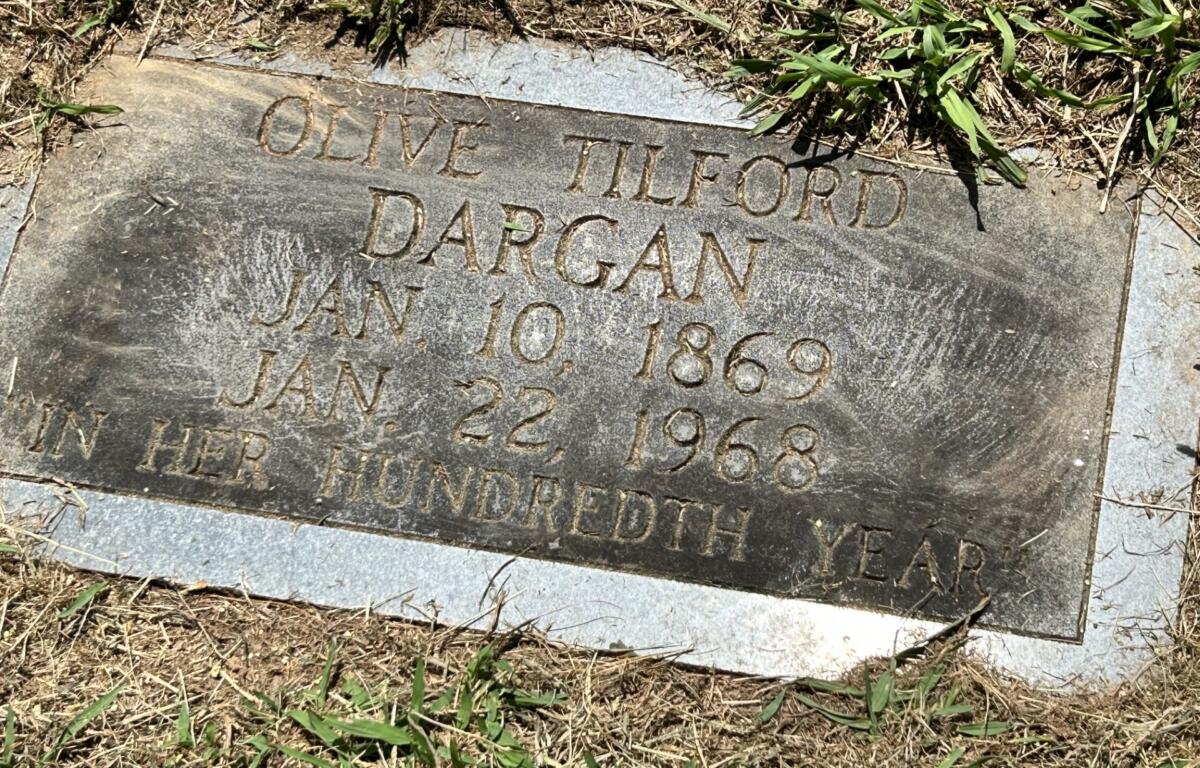

Feminist and socialist Olive Tilford Dargan (1869-1968), known for her poetry and tales of North Carolina textile strikes, is buried in Green Hills Cemetery in Asheville.

—–

According to the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame, Olive Tilford Dargan was born on a farm in Grayson County, Kentucky in 1869. Ten years later, the family moved to the Missouri Ozarks, where her parents founded a school. At 14, she became their assistant, teaching 40 students — ranging in ages from 6 to 20 — in a one-room school. At 17, she won a scholarship to Peabody College. After graduation, she taught in Arkansas and Texas before attending Radcliffe. At Radcliffe, she met Pegram Dargan, a South Carolina poet who was a senior at Harvard. After teaching in Nova Scotia for a year, she returned to Boston and renewed her friendship with Dargan. When she moved to Blue Ridge, Georgia, to write, he followed her there, and they subsequently married and settled in New York City, where they both worked as writers.

Dargan the writer

In 1915, after Pegram Dargan was lost at sea, Olive moved to a farm in Swain County near the Almond community, according to the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. Up to that time, Dargan had primarily written plays. But in 1917 she published “The Cycle’s Rim,” a series of sonnets dedicated to Pegram’s memory. The book was the last volume of poetry to receive the Patterson Cup, according to the DNCR.

The farm home in Swain County burned in 1923 and Olive moved to West Asheville in 1925, living in a log cabin she called Bluebonnet Lodge. That’s where she lived the rest of her life.

After moving to Asheville, she wrote a collection of short stories many consider her best work, “Highland Annals,” and three novels under the pen name Fielding Burke, as well as a final book of verse and a last short story collection. Dargan is widely considered to be one of the best authors ever to come out of the Appalachian South. Few have surpassed her in the description of mountain beauty or in her sympathy for the less fortunate.

In 1932, Dargan published “Call Home the Heart.” That book and its sequel, “A Stone Came Rolling,” published in (1935), portrayed mountain natives as characters lured to textile mills by the promise of prosperity, the DNCR said. These “social problems” novels were widely reviewed and commented upon. Richard Walser of North Carolina State University, the dean of the state’s literary scholars, in his standard and widely consulted Literary North Carolina (revised, 1986), wrote that, while others have written about textile strikes, “it remained for the equally sympathetic Olive Tilford Dargan to translate those convulsive times into vital literature” in her novels, the DNCR said.

Dargan provided one of the few strong southern female voices to the proletarian fiction of the 1930s, according to Appalachian State University. Much of her writing focused on women and working-class issues of the Southern Appalachian region.

“She was a feminist and a socialist, providing one of the few strong southern female voices to the proletarian fiction of the 1930s. As an active participant in the proletarian movement, Dargan wrote a series of radical feminist/socialist novels on the Gastonia mill strikes,” the ASU article said. “Dargan was one of the only proletarian writers to provide a voice of the female working-class experience. Her most well-acclaimed published work, ‘From My Highest Hill: Carolina Mountain Folks,’ was not overtly political, but concentrated on her neighbors in the mountains of Western North Carolina.”

The article went on to say Dargan was especially interested in fighting the stereotypes of mountain people and culture that were propagated in local color writings.

A North Carolina historical marker went up at the West Asheville library in 2000. Bluebonnet Lodge was torn down for office development after Dargan’s death in 1968.

According to NCpedia.com, Dargan died at her home in Asheville after an active life of almost a century.

MORE TOMBSTONE TALES:

Father-in-law of famous evangelist buried in WNC

Beloved photographer buried in Asheville

The final resting place of a music pioneer

Daredevil pilot buried in Black Mountain

A resort, the Civil War, a book and 2 cemeteries

Revolutionary War heroes buried in Asheville

Bill Nye the Humor Guy buried in Fletcher

‘American Godfather’ buried at Riverside

‘The Gift of the Magi’ author buried in Asheville

Former slave, Union soldier buried in Asheville

1st female legislator in the South buried in Asheville

Actress, activist Dorothy Hart buried in Asheville