EDITOR’S NOTE: Strangeville explores the legends, folklore, and unexplained history of Western North Carolina. From Cherokee mythology and Appalachian ghost stories to Bigfoot sightings and UFO encounters, the Blue Ridge Mountains have long been a hotspot for the strange and mysterious. Join us as we dig into the past and uncover the truth behind the region’s most curious tales.

*************

MORGANTON, N.C. — The old Broughton Hospital in Morganton remains a fixture on campus, its imposing frame a quiet witness to more than a century of whispered stories, suffering, and mysteries.

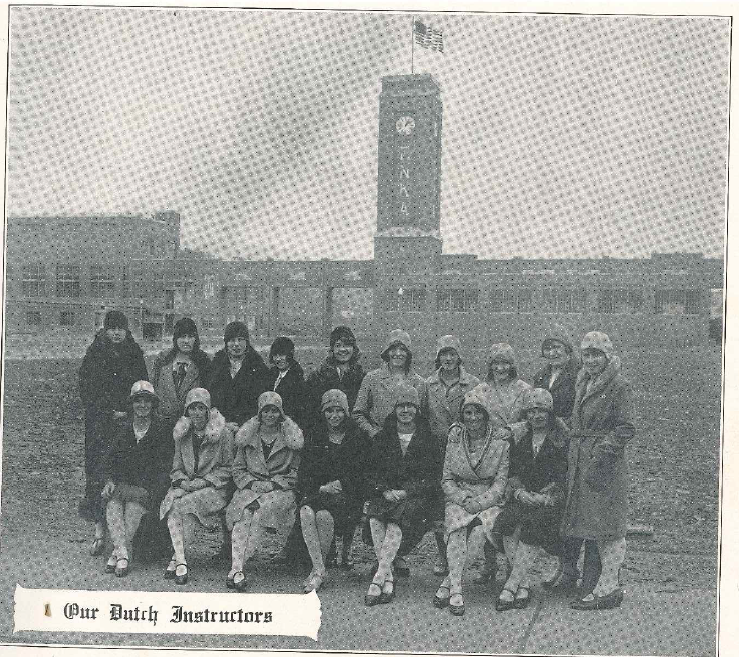

The psychiatric hospital, one of North Carolina’s oldest, opened in 1883 as the Western North Carolina Insane Asylum. It was built according to the Kirkbride Plan, a 19th-century philosophy that imagined beauty, natural light, and symmetry as part of a cure for mental illness. Tragically, what was meant to be a place of hope became a place of fear.

Overcrowding, forced institutionalization, and controversial treatments like hydrotherapy, electroshock, and lobotomies became part of daily life for many patients. In time, the hospital’s haunted reputation took hold.

Former staff members and visitors have long told of unexplained footsteps in empty wings, shadow figures in patient wards, and disembodied voices echoing through the night. Some say the Kirkbride building is one of the most active paranormal sites in the state. Others insist the real horror is in the history.

Among those who worked at Broughton, few chronicled its supernatural side as thoroughly as Margaret Langley, who collected firsthand accounts of paranormal encounters from coworkers across decades. In Ward 27 South, she and a fellow nurse watched in stunned silence as a dense, misty cloud floated down the hallway before vanishing. In the employee cafeteria, phantom piano music was heard late at night, doors opened and closed on their own, and names were whispered when no one else was present.

During the early 2010s, as construction crews worked on a new building adjacent to the historic hospital, workers shared similar stories. One man reported hearing bloodcurdling screams in the utility tunnels below ground. Another, welding on the roof, claimed the screams were so loud they pierced his protective gear—though no one else was nearby.

A Hidden Legacy of Eugenics

In the early 20th century, Broughton became one of several institutions in North Carolina tied to the state’s eugenics program. Patients deemed “unfit” for reproduction, including those diagnosed with schizophrenia, depression, or intellectual disabilities, were sterilized without their consent. Records show that between the 1930s and 1970s, more than 7,600 North Carolinians were subjected to forced sterilization including many Broughton patients.

For years, this dark chapter remained buried in medical archives. In 2002, Gov. Mike Easley officially apologized to victims, making North Carolina one of the few states in the nation to apologize for eugenics practices.

A Tragedy Behind Locked Doors

For decades the horror inside Broughton continued as violence, loss, and unanswered questions unfolded behind closed doors.

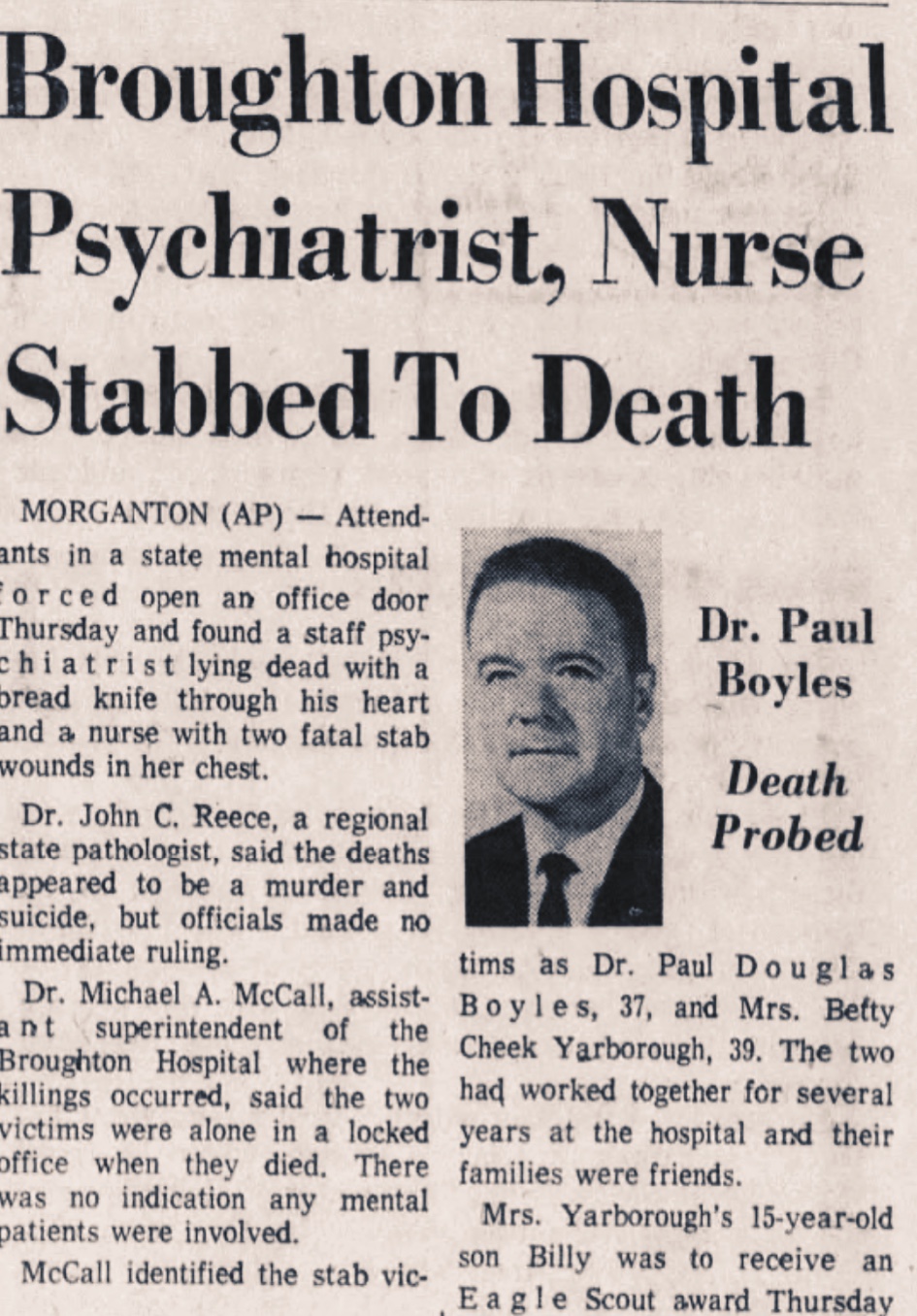

One of the most shocking events in Broughton’s history came in the early morning hours of April 22, 1971. Dr. Paul Douglas Boyles, a 37-year-old psychiatrist, and 39-year-old nurse administrator Betty Cheek Yarborough were found stabbed inside a locked room on Ward R.

They had been seen entering the nurse’s station around 7:30 a.m. A commotion followed, then silence. When hospital staff forced the door open, they found Boyles dead with a serrated bread knife through his chest. Mrs. Yarborough was barely alive but died one hour later.

Initial confusion gave way to years of speculation. Some believed Betty had attacked Dr. Boyles. Others whispered of a romantic affair that ended in violence. Official findings ended the debate: the Burke County Medical Examiner ruled Betty Yarborough’s death a homicide, and Paul Boyles’ death a suicide.

Still, the questions linger. No motive was made public. No detailed findings were ever released. The only certainty is that two lives ended violently inside a hospital built for healing.

In the aftermath of the 1971 tragedy, whispers of something lingering took hold. Employees spoke of angry voices behind locked office doors, only to find the rooms empty. A sudden drop in temperature near old filing cabinets gave some the sense they were not alone. Others glimpsed shadowy figures—one in a white coat, another in a nurse’s uniform—appearing just long enough to be doubted. Decades later, current and former employees have expressed their belief that the air feels heavier in the areas connected to this tragedy, as if something unfinished remains.

The Twins Who Died Together

Nearly a decade earlier, in April 1962, another unexplained death stunned Broughton’s staff, and it remains unsolved to this day.

Identical twin sisters Bobbie Jean and Betty Jo Eller, both 31, were found dead in their beds in separate wards of the hospital. They had been separated the day before because one was considered a dominating influence over the other.

One twin was discovered dead early in the morning. A staff member rushed to check the other and found her dead too. There were no signs of trauma. Autopsies revealed no anatomical cause of death. Both had been prescribed medication, but nothing in toxicology suggested an overdose.

Dr. John C. Reece, Burke County’s coroner at the time, considered an eerie theory: the women had willed themselves to die. “They could have died at the same time,” he told reporters. “Psychiatrists tell me that some psychotics, especially schizophrenics, have a will not to live.”

Born as triplets, only two survived infancy, the Eller sisters had struggled with schizophrenia for years. Their story faded from headlines, but among longtime staff and local historians, the strange timing of their deaths remains a disturbing mystery.

Some staff members believe the twins never truly left. In the ward where Bobbie Jean died, patients later reported a glowing blue orb outside the dayroom windows, flickering through the trees. One patient claimed she was pushed from her bed by invisible hands; another felt her ankle tugged and snapped. In the ward where Betty Jo passed, nurses have described the persistent feeling of being watched when completely alone. Residents and employees have suggested the twins may still be causing harmless mischief in the afterlife.

A Place That Remembers

Today, the original Kirkbride building is used as office space. A new hospital opened nearby in 2019, offering modern facilities and care. But the history hasn’t gone anywhere.

The old cemetery behind the building holds more than 1,500 graves. For decades, many were marked only by numbers. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, chaplains and volunteers began identifying those buried there, placing nameplates where anonymity once reigned.

Still, the stories persist. Whispers of piano music echoing through sealed rooms. Reports of a woman in white watching from a third-floor window. Others describe the silhouette of a figure hanging in a high window said to be the spirit of a patient who died by suicide in a stairwell decades ago. Drivers passing along Highway 18 reported seeing her so frequently that hospital staff eventually boarded up the window.

Broughton Hospital is a historic landmark, institution of care, and a symbol of how far mental health treatment has come. It is also a place shaped by tragedy, loss, and unanswered questions.