EDITOR’S NOTE: Strangeville explores the curious and unexplained stories that have long defined Asheville and Western North Carolina. The region is full of unanswered questions, from old folklore and local legends to eerie encounters, unsolved moments in history, and the true-crime mysteries that still leave people wondering. Each week, we look back with an open mind and a sense of curiosity, trying to understand why some stories take hold and why some can never be explained.

How does a fire burn for more than 150 years without going out?

That question has followed William “Billy” Morris for generations in the foothills near Saluda, where locals say he inherited responsibility for a family hearth fire kept alive from the Revolutionary era until his death in 1944.

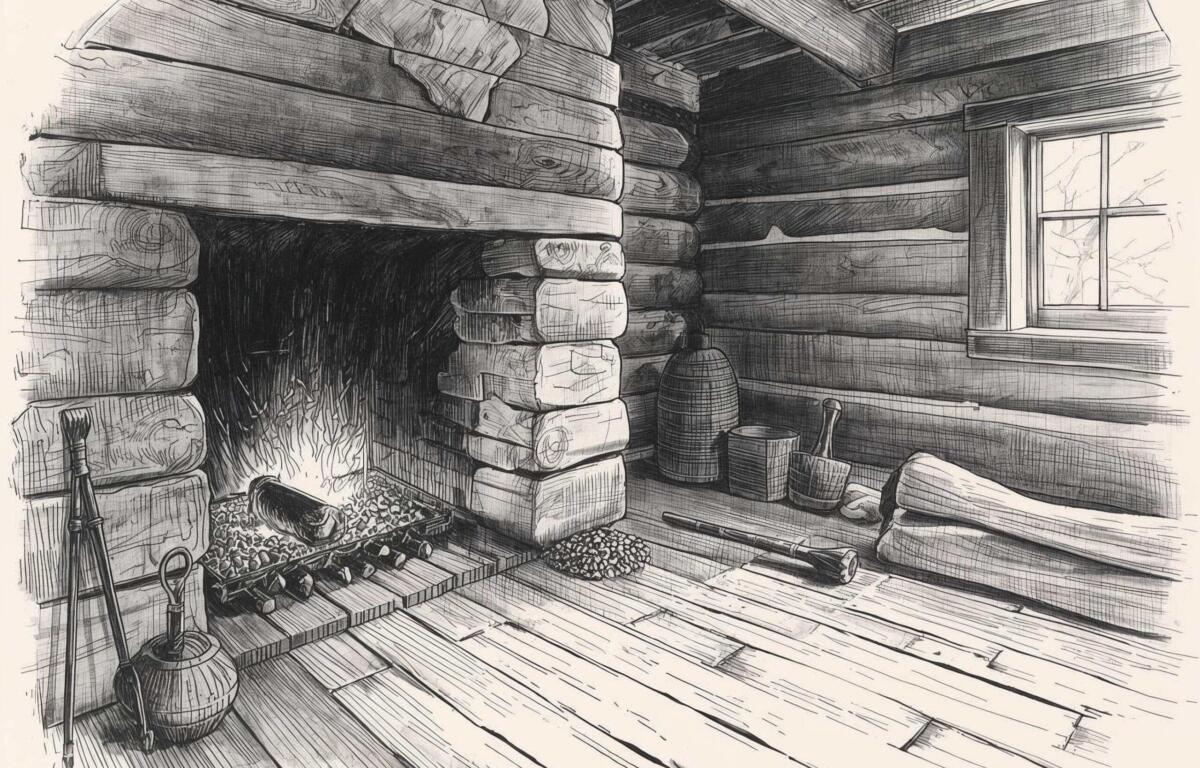

Morris, a lifelong bachelor, lived simply in a log cabin near Holbert Cove Road. By the time he died, the fire in his fireplace had been kept alive, without being fully extinguished, since 1780. The claim made Morris a regional curiosity and earned him a nickname that has endured for decades: the Keeper of the Century-Old Fire.

The details vary, but the story repeated for generations is consistent. Morris inherited responsibility for a family hearth fire that earlier generations treated as continuous. It was never allowed to go cold. When it burned low, it was banked under ash, and when it faltered, hot coals were revived rather than replaced.

By 18th- and 19th-century standards, the practice was not unusual. Before matches became common, Appalachian families treated fire as a resource that could not be wasted, preserving embers overnight and sharing live coals with neighbors rather than starting over.

What made Morris unusual was persistence. Local accounts describe a man who lived alone, without electricity, and organized his days around the hearth. The fire heated his cabin and was used to cook his food.

By the 1930s, the story had traveled far beyond Saluda. Community histories report that Morris was invited to New York City to appear on the national radio program “We the People,” which featured Americans with unusual lives.

Local accounts do not explain how the fire was tended while Morris traveled to New York, though Appalachian practice at the time commonly involved temporary caretaking. Neighbors or relatives would have tended the hearth while Morris was away.

Morris died in 1944 at age 84. According to locals, the fire went out that same year. The next person tasked with keeping it became ill and could not maintain it.

The fire survived as long as it did because someone chose, day after day, not to let it go out. When Morris was gone, the fire finally went out as well.