Editor’s Note: Western North Carolina is rich with untold stories—many resting quietly in local cemeteries. In this Tombstone Tales series, we explore the lives of people from our region’s past whose legacies, whether widely known or nearly forgotten, helped shape the place we call home.

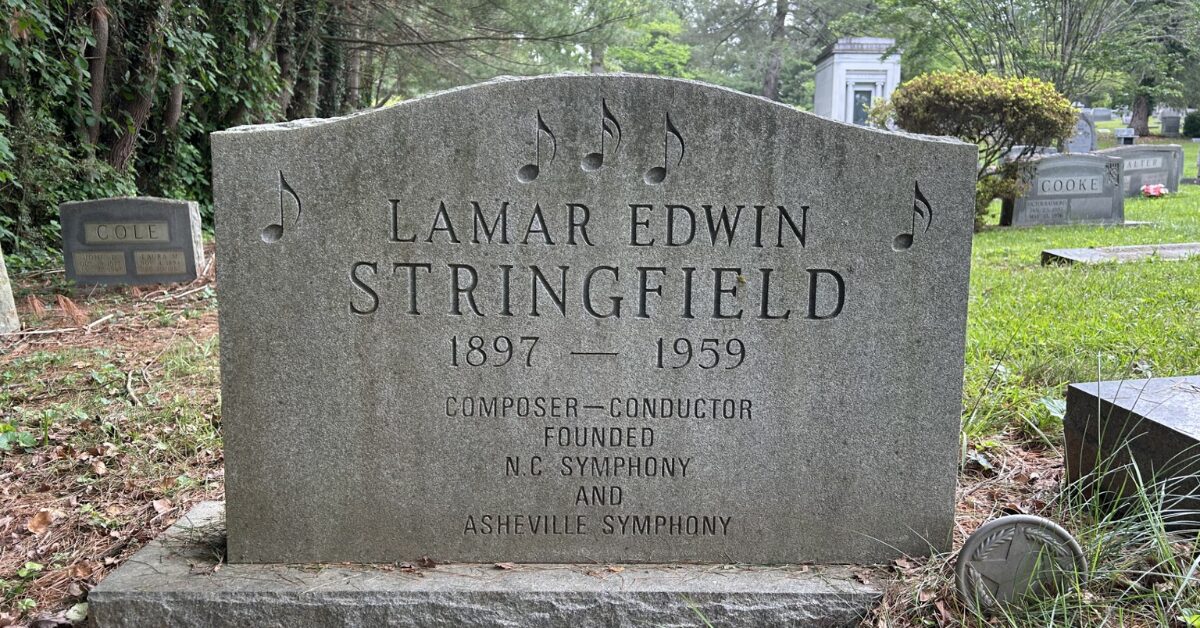

ASHEVILLE, N.C. — Amid the rolling landscape of Asheville’s Riverside Cemetery rests Lamar Edwin Stringfield, a composer and conductor who carried the songs of the southern mountains into the world of orchestral music.

Born near Raleigh in 1897, Stringfield grew up in western North Carolina, where the rhythms of mountain life and music shaped his imagination. The son of a Baptist minister, he learned piano, banjo and cornet as a child and later studied at Mars Hill College and Wake Forest College before enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1916. He served with the 105th Engineers Band in France during World War I and, after the armistice, studied flute and composition in Paris before completing his training in New York at the Institute of Musical Art, now Juilliard.

In 1920 he helped found the New York Flute Club and began writing orchestral works that reflected both his classical training and his Carolina roots. His early compositions revealed his affection for home. His orchestral suite From the Southern Mountains, written in 1927, earned him national recognition the next year and established his reputation as a serious composer. Rather than settle in New York, he chose to return to North Carolina..

In 1929, Stringfield collaborated with folklorist Bascom Lamar Lunsford to publish Thirty and One Folk Songs from the Southern Mountains. Lunsford collected the songs and Stringfield arranged them for piano and voice, preserving melodies that might otherwise have disappeared. Their partnership linked oral tradition with written composition and influenced generations of southern musicians and scholars.

Two years later, Stringfield founded the Institute of Folk Music at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, one of the first programs in the country to treat regional song as serious study. In 1932 he organized the North Carolina Symphony and served as its first conductor, taking orchestral performances to towns and schools across the state and giving many North Carolinians their first experience of live symphonic music.

Over his lifetime, Stringfield composed hundreds of works, from chamber pieces to large-scale suites and scores for radio and outdoor drama. His arrangements of Appalachian tunes brought a regional sound to audiences that might never have heard it otherwise.

Stringfield’s later years were quieter. Illness and financial strain followed him back to Asheville, where he continued composing until his death on Jan. 21, 1959, at the age of 61.

Today, his legacy is written across North Carolina. The symphony he founded still performs statewide. His song collection with Lunsford remains a vital link to early mountain music. The notes carved into his headstone in Riverside Cemetery stand as a reminder of a man who believed the folk melodies of his home were worthy of the concert stage.