Editor’s Note: Western North Carolina is rich with untold stories—many resting quietly in local cemeteries. In this Tombstone Tales series, we explore the lives of people from our region’s past whose legacies, whether widely known or nearly forgotten, helped shape the place we call home.

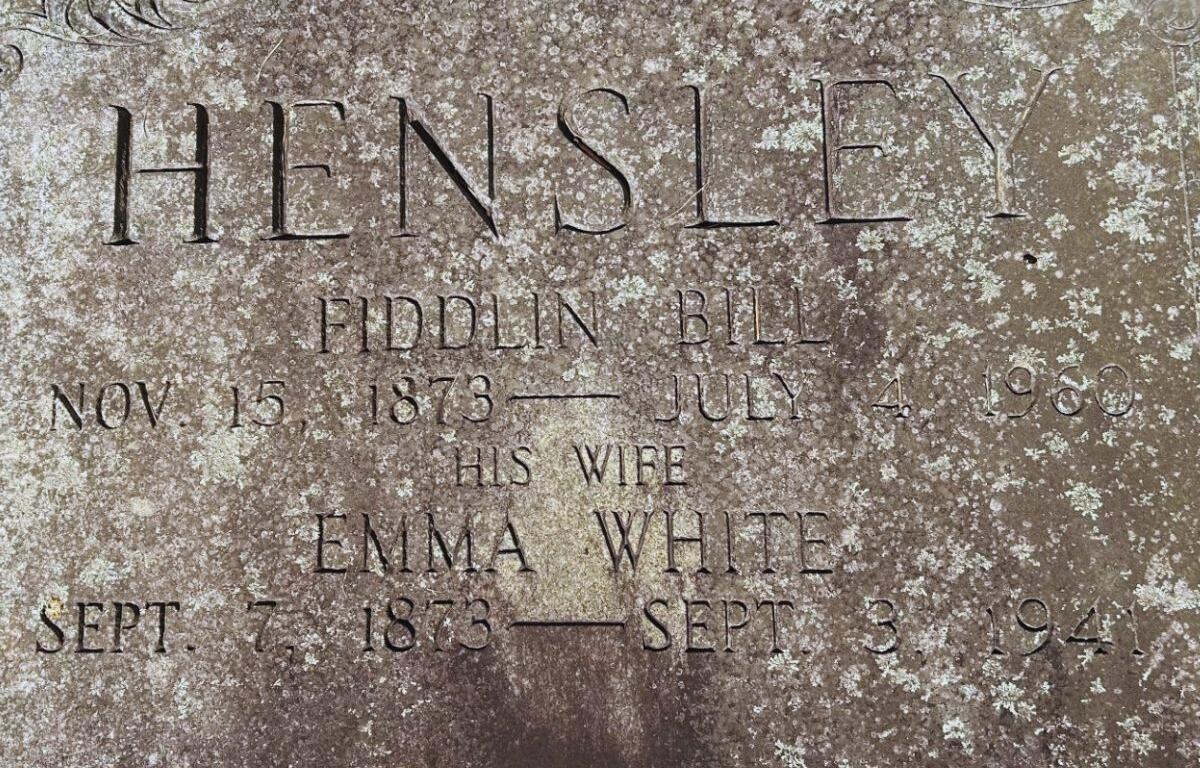

SKYLAND, N.C. – The headstone for William Andy “Fiddlin’ Bill” Hensley at New Salem Baptist Church Cemetery may be simple, but the man it honors helped shape the sound of Southern Appalachia.

Known for his skill with a fiddle and his deep roots in mountain tradition, Hensley carried old-time music from rural North Carolina onto radio broadcast, festival stages, and film sets.

Born in Happy Valley, Tennessee, in November 1873, Hensley’s family moved to Western North Carolina when he was a young boy. He once recalled walking 85 miles over the mountains to their new home, carrying a rooster under one arm and leading a dog with the other. From those humble beginnings, he became one of the region’s most celebrated fiddlers.

Hensley’s musical lineage ran deep. He learned to play by ear, studying the styles of his father, grandfather, and uncles Mac and Rube Hensley. He was also mentored by notable regional musicians, including fiddle makers George and Hugh Bell, and Blind Wiley Laws. He eventually acquired a prized fiddle from Tennessee’s fiddling Governor Bob Taylor—an instrument he called “Old Calico.”

In an era before widespread recordings, Hensley’s music was heard wherever people gathered. He played at log raisings, corn huskings, church socials, and quilting bees. His joyful, rhythmic style made him a local favorite and later drew the attention of Bascom Lamar Lunsford, founder of Asheville’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival. Hensley became a frequent performer there, helping preserve and promote traditional Southern Appalachian music.

His fame extended beyond the mountains. Hensley performed at the National Folk Festival and on radio programs in New York. He even appeared in early Hollywood films, showcasing his talent for a national audience. Despite his acclaim, he remained rooted in Buncombe County, often playing alongside fellow mountain musicians like Osey Helton.

Hensley’s contribution to folk music was documented by folklorists including David Parker Bennett, Jan Philip Schinhan, Jerry Wisner, and Artus Moser. These recordings and interviews preserved his repertoire for future generations and helped cement his status as one of the foundational figures in American old-time music.

Hensley died on July 4, 1960, in Canton, North Carolina. He was laid to rest at New Salem Baptist Church Cemetery in Skyland, not far from the hills that shaped his sound and spirit.

Today, the grave of Fiddlin’ Bill Hensley sits quiet and untended, the headstone now toppled. Once a site where musicians and folk music lovers left fiddle strings, coins, or notes in tribute, there are no tokens now. Still, Hensley’s spirit lingers in the music of these mountains. As he once said, he never needed sheet music because “the hills had already written the songs.”

Visit New Salem Baptist Church Cemetery in Skyland

-

Tombstone Tales: Flat Rock’s Slaves and Freedmen Memorial

Beneath a quiet stand of trees near Flat Rock’s oldest Episcopal church, a granite cross rises above a hillside of small white markers. It is one of the few memorials dedicated to enslaved and freed African Americans in Western North Carolina.