Editor’s Note: Western North Carolina is rich with untold stories—many resting quietly in local cemeteries. In this Tombstone Tales series, we explore the lives of people from our region’s past whose legacies, whether widely known or nearly forgotten, helped shape the place we call home.

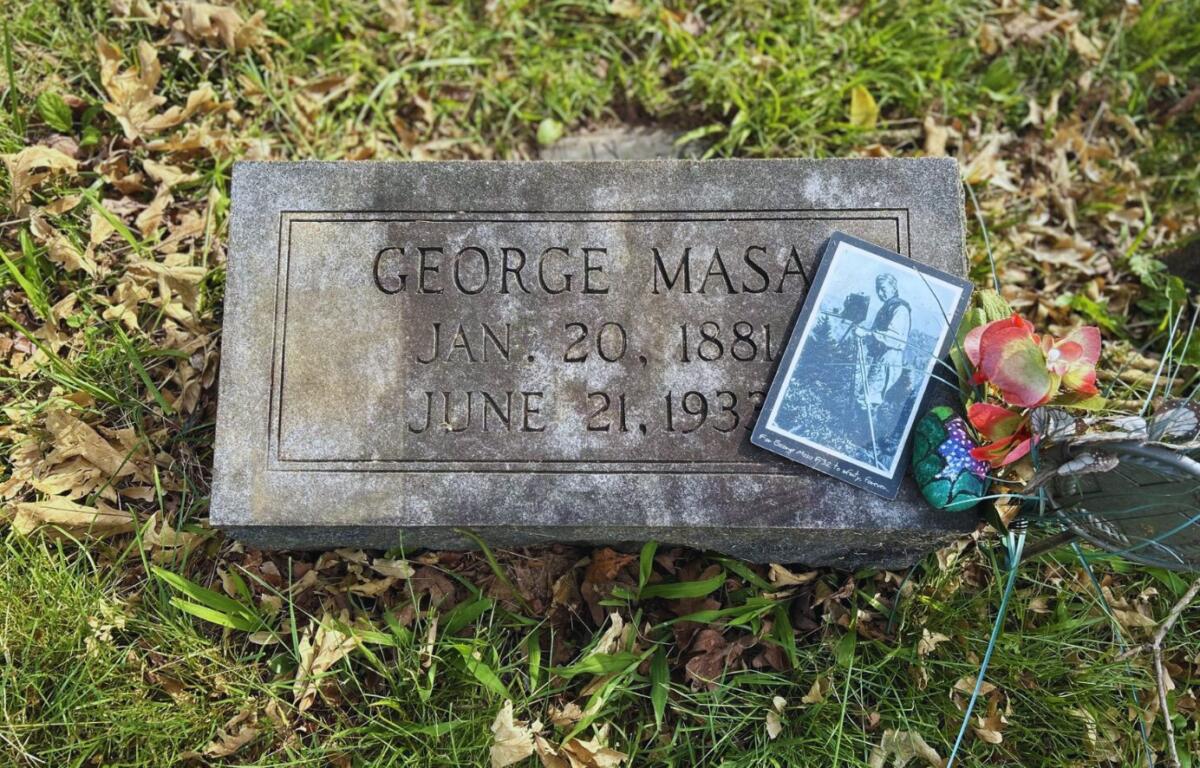

ASHEVILLE, N.C. — At Riverside Cemetery in Asheville rests the modest grave of George Masa, a man whose camera captured vistas that helped redefine how America saw the wilderness of the southern Appalachians. Born Masahara Iizuka in Japan around 1881, he arrived in Western North Carolina in the mid-1910s and over the next two decades transformed from a hotel valet into one of the region’s most influential photographers and conservation advocates.

Masa came to Asheville about 1915 and took a job at the Grove Park Inn, first working in the laundry and then as a valet. His fascination with photography began there, developing film for wealthy hotel guests and borrowing a camera from the inn’s manager. Within a few years, he opened his own photography business, Plateau Studio, serving Asheville’s growing tourist community. His landscape postcards and prints became popular keepsakes for visitors exploring the Blue Ridge.

Masa’s true vision took shape in the rugged terrain of the Great Smoky Mountains, carrying a large-format camera, tripod and glass plates as he hiked the mountains. He often waited for days for the right light for his panoramic images of ridgelines, waterfalls and forest light. His photographs helped rally support for protecting the region’s wilderness from logging and development.

Masa’s friendship with writer Horace Kephart deepened his conservation work. Together they mapped remote peaks, traced possible routes for the Appalachian Trail, and helped name dozens of features in the Smokies. Using a homemade odometer built from a bicycle wheel, Masa meticulously measured trail distances, a mix of artistry and engineering that reflected his devotion to accuracy.

His photographs became vital evidence in the campaign to create the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The clarity and grandeur of his work helped convince federal officials and donors that the area’s scenic and ecological value merited protection. Yet despite his role in shaping the park’s future, Masa lived modestly, and the Great Depression devastated his business.

By 1933, Masa was penniless and ill. He died of tuberculosis at age 52 in a sanitarium near Asheville. Friends from local hiking clubs paid for his funeral, and he was buried at Riverside Cemetery. The national park he worked so hard to see created was formally established the following year.

A 5,685-foot peak in the Smokies now bears his name, Masa Knob, and his photographs are preserved in collections across the region.

Masa was a man whose vision brought people together and a meticulous craftsman whose quiet work helped define one of America’s greatest parks. His story, like his photographs, reflects both the beauty and endurance of the mountains he loved.

Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina

-

Tombstone Tales: Flat Rock’s Slaves and Freedmen Memorial

Beneath a quiet stand of trees near Flat Rock’s oldest Episcopal church, a granite cross rises above a hillside of small white markers. It is one of the few memorials dedicated to enslaved and freed African Americans in Western North Carolina.