Editor’s Note: Western North Carolina is rich with untold stories—many resting quietly in local cemeteries. In this Tombstone Tales series, we explore the lives of people from our region’s past whose legacies, whether widely known or nearly forgotten, helped shape the place we call home.

HAYWOOD COUNTY, N.C. — Scattered across cemeteries in Western North Carolina are headstones unlike the polished granite slabs most visitors expect to see. Built from concrete with river stones, glass or tile, these handmade markers reflect a period when families created their own memorials using whatever materials were close at hand.

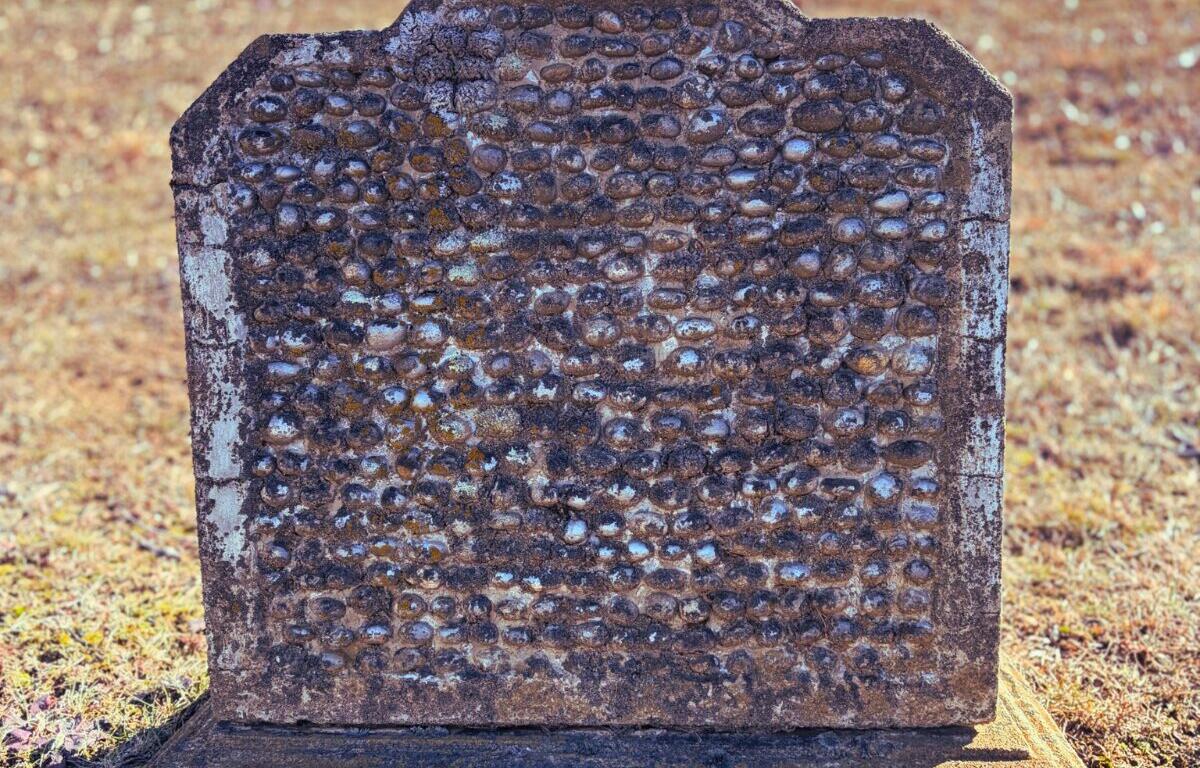

One such marker, belonging to Thomas Cane Goodson, stands in Bethel Community Cemetery in Canton. The marker design mirrors another handmade grave that was featured in October in Waynesville’s Green Hill Cemetery. While created by different families, both markers reflect a shared mountain tradition of folk memorials shaped by necessity, skill and devotion.

Goodson’s grave is constructed of poured concrete embedded with rows of stones. His name and dates are carved directly into the surface. At the base of the marker, a recessed opening was built into the structure, intended as a place for flowers or small tributes. The back of the monument is covered in the same stonework as the front, an added detail that required time and care.

Goodson was born May 3, 1879, in Haywood County, according to state records. He was a Haywood County native who worked as a laborer and spent his life in the same mountain communities where he was later buried.

He died on Oct. 31, 1936, at Haywood County Hospital. His death certificate lists tuberculosis of the lungs as the principal cause, with the illness recorded as lasting several months or longer. In the 1930s, tuberculosis was a slow and often devastating disease. Long hospital stays were costly for working families.

For many Appalachian households, prolonged illness meant lost income and financial strain. Traditional carved stone markers were expensive, and families often turned to handmade memorials made of local materials. River stones were gathered, cleaned and carefully set into wet cement, creating monuments that were both durable and deeply personal.

Though often overlooked, these markers are part of a broader burial tradition found throughout Appalachia. They appear in small churchyards, family plots and rural cemeteries.

Nearly 90 years after Thomas Cane Goodson’s death, his handmade marker remains a reminder that some of the region’s most meaningful memorials were not bought from a catalog but built by hand, one stone at a time.