Editor’s Note: Western North Carolina is rich with untold stories—many resting quietly in local cemeteries. In this Tombstone Tales series, we explore the lives of people from our region’s past whose legacies, whether widely known or nearly forgotten, helped shape the place we call home.

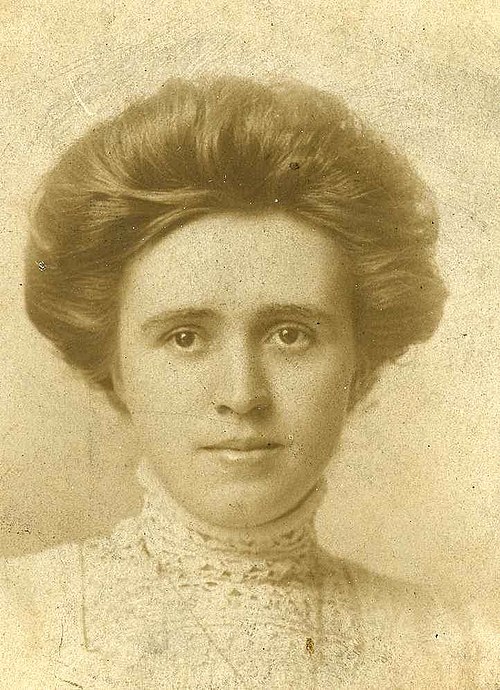

ASHEVILLE, N.C. — Long before women had the right to vote in North Carolina, Lillian Exum Clement Stafford made history by winning a seat in the state legislature. She did it in 1920 becoming the woman in the South to hold state legislative office and the first woman elected to the North Carolina General Assembly.

She was just 26.

Clement was born in Black Mountain in 1894. Her family later moved to Asheville, where she studied law under two local attorneys, J.J. Britt and Robert Goldstein. She worked as an office deputy in the Buncombe County sheriff’s department, and while still in her early twenties, passed the North Carolina bar exam.

In 1917, she opened her own law office, making her the first woman in North Carolina to establish a solo criminal law practice.

Her skills and confidence in court gained her respect quickly. She became known for her thorough preparation and her ability to argue clearly before a judge or jury. During World War I, she served as chief clerk for the Buncombe County draft board, managing local military service records and responsibilities.

In 1920, Clement ran for a seat in the North Carolina House of Representatives. It was the same year the 19th Amendment was ratified, though North Carolina had not yet approved it. That meant she ran in a statewide election before women were even granted the right to vote in the state.

She won the Democratic primary and defeated her male opponent in the general election, receiving more than 10,000 votes to his 41.

When the General Assembly convened in Raleigh in January 1921, Clement took her seat. As the only woman in the House, she was nicknamed “Brother Exum” as a form of collegial respect. There was no precedent for how to address a female legislator in Raleigh at the time and the standard practice for members of the legislature was to refer to one another as “Brother (Last Name).”

Though it may sound unusual today, the nickname “Brother Exum” became a sign of the respect she commanded in a space where women had never held office before.

She introduced 17 bills during her first and only term and 16 of them passed.

Following her 1921 marriage to newspaperman E. Eller Stafford, she did not run for re-election. Instead, she focused on her work and her family, and in 1923, she gave birth to a daughter, Nancy.

Stafford’s life was cut short just two years later. When she died of pneumonia on February 21, 1925, at age 31, both houses of the General Assembly passed resolutions honoring her life and service.

She was buried in Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, not far from where she grew up.

Visitors walking the quiet paths of Riverside Cemetery today might pass her grave unaware of the doors she opened. But for anyone who has worked for change or stood alone in a room where they weren’t expected, her story still resonates.

She didn’t just make history. She helped rewrite who could make it. In doing so, she left behind a legacy of a life lived with boldness and purpose.

Visit Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina

-

Tombstone Tales: Flat Rock’s Slaves and Freedmen Memorial

Beneath a quiet stand of trees near Flat Rock’s oldest Episcopal church, a granite cross rises above a hillside of small white markers. It is one of the few memorials dedicated to enslaved and freed African Americans in Western North Carolina.